Episode four of the second season of Free the Seed! the Open Source Seed Initiative podcast

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 46:05 — 50.8MB) | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

This podcast is for anyone interested in the plants we eat – farmers, gardeners and food curious folks who want to dig deeper into where their food comes from. It’s about how new crop varieties make it into your seed catalogues and onto your tables. In each episode, we hear the story of a variety that has been pledged as open-source from the plant breeder that developed it.

In this episode, host Rachel Hultengren talks with Patrina Nuske Small and Craig LeHoullier about the Dwarf Tomato Project, a collaborative, all-volunteer tomato breeding project. We discuss how the project came about, the benefits and challenges of having an all-volunteer team, and the pleasant surprises of plant breeding.

Patrina Nuske Small; ‘Uluru Ochre’

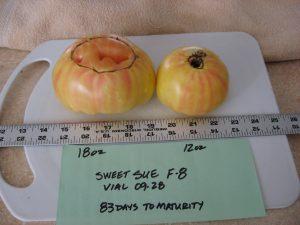

Craig LeHoullier; ‘Dwarf Sweet Sue’ (photo credit: Paul Fish)

Episode links

– To learn more about the Dwarf Tomato Project and find information about buying seeds of the dwarf tomato varieties that have come out of the project, check out the project’s website: https://www.dwarftomatoproject.net/

– Craig LeHoullier’s website: https://www.craiglehoullier.com/dwarf-tomato-breeding-project

– Seed Savers’ Exchange: https://www.seedsavers.org/

– Tomatoville Gardening Forums: http://tomatoville.com/

Let us know what you think of the show!

Free the Seed! Listener Survey: http://bit.ly/FreetheSeedsurvey

Free the Seed!Transcript for S2E4: The Dwarf Tomato Project

Rachel Hultengren: Welcome to episode four of the second season of Free the Seed!, the Open Source Seed Initiative podcast that tells the stories of new crop varieties and the plant breeders that develop them. I’m your host, Rachel Hultengren.

In this episode, I talk with Craig LeHoullier and Patrina Nuske Small, the co-creators of the Dwarf Tomato Project, the “first all-volunteer world-wide tomato breeding project in documented gardening history”. We discuss how the project came about, the benefits and challenges of having an all-volunteer team, and the pleasant surprises of plant breeding.

Patrina Nuske Small began gardening in her 50’s after graduating from Flinders University in South Australia, realizing that it was time to get away from research and spend more time outside in the fresh air. Patrina is currently based in New South Wales.

Dr. Craig LeHoullier followed a 25 year career in pharmaceuticals with an ongoing writing career that includes Epic Tomatoes and Growing Vegetables in Straw Bales. He maintained a parallel obsession with gardening, first with heirloom tomatoes, then with amateur breeding. Craig joined Seed Savers Exchange in 1986, and serves as an adviser to the Exchange for tomatoes. Craig is based in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Rachel Hultengren: Patrina, Craig, welcome to the show!

Patrina Nuske Small: Thanks, Rachel!

Craig LeHoullier: Thank you very much, Rachel – it’s an absolute delight to be able to do this today.

Rachel Hultengren: Craig, maybe you can start by briefly telling us about the Dwarf Tomato Project. What is the project, and what are its goals?

Craig LeHoullier: The project is huge, fascinating, endlessly surprising. To put it all in a sentence, the goal of the Dwarf Tomato breeding project was to offer to the gardening community the largest possible selection of interesting, delicious tomato plants that can be grown by space-challenged gardeners, while at the same time provide a fascinating project for those wishing to become involved in to experience. And in that respect, I think we haven’t only checked all the boxes we set out to check, but we’ve checked boxes that we never thought we were going to check.

Rachel Hultengren: Patrina, how did the project get started, and when did it get started?

Patrina Nuske Small: In 2005, I was searching the internet for gardening information because I really needed to, like I say, get outside in the fresh air and get away from books. And I found a tomato forum, and I thought that was really odd, how you could have a whole forum on tomatoes. And once I was in there, I found out so many interesting things. And Craig was one of the main posters, and one day he pointed out that we’ve got, you know, thousands of heirloom varieties of tomato, but the dwarf category is just so limited to, usually, small red tomatoes. And wouldn’t it be great if we could just do some crosses with heirlooms and dwarfs?

And I thought that sounded like a really fun thing to do. And I thought, “Right. I’m going to grow some dwarfs next season, and I’m growing some heirloom varieties, and I’m going to have a go at crossing some tomatoes.” And I loved biology in high school, so it was a really fun thing for me to do. And I was successful, and we started off with eight crosses, which we named after [Snow White and] the Seven Dwarfs, and we added another one called Witty, because we needed to have names for the hybrids for ease of reference. And I sort of collaborated with Craig, and we organized to start teams – one in the Northern Hemisphere, one in the Southern Hemisphere – so we could grow two seasons in a year, and the project was born!

Craig LeHoullier: Patrina opened this up really wonderfully. And I think, in parallel… my wife and I have been selling heirloom tomato seedlings for, at the time, about 15 years here in Raleigh [North Carolina], and the most frequently asked question was always, “You know, I love ‘Cherokee Purple’ and I love ‘Sungold’, but these things get 8 or 10 feet tall, and they go all over the place, and I need to garden on my deck or my patio or my driveway or I’ve got a physical issue that means I have to deal with smaller plants.” So at the same time Patrina got that spark about crossing varieties of heirlooms with dwarfs, the need was showing up for my end of being able to tell my customers, “We do have interesting, colorful, delicious, large-fruited, worthwhile varieties that will excel in a small container.” And you can use useless tomato cages, those wire cone shaped things that people put on their indeterminates and then throw up their hands after a few weeks. They’re perfect for the dwarfs. So in a way, I think, Patrina and I were meant to meet when we did and do this project when we did, because it is serving a lot of gardeners who otherwise, you know, they would struggle to grow tomatoes if they didn’t have these shorter varieties to pick from.

Rachel Hultengren: You used the word indeterminate, Craig, for some of the tomatoes. And, so, tomatoes can come in an indeterminate or a determinate variety, and maybe you could remind our listeners what those terms mean, and then how those differ from dwarf varieties?

Craig LeHoullier: Sure. Well, the main collection of tomatoes – probably 98% – are indeterminate, meaning they grow vertically, they sucker at every intersection between a main stem and the leaf junction (suckers are just additional fruiting main stems) until they’re killed by frost or disease. So conceivably a tomato that is indeterminate can reach 10, 15, 20, 25 feet in length, 3 to 6 feet or more in girth, and just be incredibly complex, out-of-control plants.

The determinate gene really showed up for the first time in the 1920’s and a lot of the modern hybrids are determinates, in which they reach a height of about 3 to 4 feet, they throw out tons of blossoms, they fruit within about a 2 to 3 week period, and then they’re pretty much done. So people think of a tomato like ‘Roma’. It’s a tomato machine for a short period of time; you make your sauce or you do your canning. But because there are so many fruit in ratio with the amount of foliage, the flavor potential of determinates tends to be inferior to that of indeterminates.

Dwarf is the third type of tomato, that just never got a lot of attention because there were so few of them around. But they combine the best traits of indeterminates, in having the ability to fruit until they’re killed by frost, with the short stature. What I like to tell my customers is, “A dwarf if a tomato that grows at half the vertical rate of an indeterminate”. So if you have a Cherokee Purple that’s 8 feet tall in your garden at the end of the season, the dwarf is going to be 4 feet tall, which means it’s easier to contain. One of the benefits is that they really don’t have to be pruned. But they do fruit gradually, and because the fruit to foliage ratio is much more in line with an indeterminate, with a dwarf you have the flavor potential there, which can equal the best of the indeterminates in the dwarf lines, something that Patrina demonstrated with one of her very first crosses, which we’ll get to – the Sneezy cross. Everything that’s popped out of that cross has been utterly delicious, and it’s not a surprise, because one of the parents – ‘Green Giant’ – is one of the best varieties we’d ever eaten.

Rachel Hultengren: Can any tomato be made into a dwarf variety?

Patrina Nuske Small: Uh, yes. The thing is here, and this is one of the fun things about this project, is that we were dealing with recessive traits as well as dominant traits. Dwarfism is a recessive trait, whereas the normal regular heirloom varieties, their dominant genes means that they grow so big and tall. So if you combine anything with a dwarf plant, you will get some recessive genes in the pool. So the first generation, which is the F1 generation, the dominant trait will show up only. You will not see any dwarfs in that generation; you’ll only see non-dwarfs. But in the second generation, they start dividing up between dwarfs and non-dwarfs, and you’ll get approximately 25% that are dwarfs, compared to 75% that are not dwarfs. And of those non-dwarfs, also, in the third generation you can still find a few dwarfs. So that was really interesting learning for the people in the project to see that come about.

Craig LeHoullier: So I think that Patrina touched on something that’s really really important. We were all pretty much amateur gardeners who, maybe some of us had science backgrounds, but I think what we had in common was we loved to garden, and we were either very or reasonably good at making observations and keeping track of things, but it was this love of the unknown. So even to this day, 13 years after we started this project, whenever we do a cross and we grow it out, we’re still learning about what’s dominant and what’s recessive. When you cross a green one and white, what happens? When you cross a white with a pink? Scientists have recorded some of these down in scientific papers, but gardeners had never really experienced and seen these first hand.

One of the challenges I’m facing, because what I’m trying to do is get a book written about this project, but how to cover genetics in a way that a layman will find fascinating. You don’t get into the weeds of genetics, yet you’re finding all of the wonders of the things that we’ve discovered doing this work over the past 13 years.

Rachel Hultengren: It sounds like it’s been quite a learning opportunity for everyone involved.

Craig LeHoullier: Yes. Wouldn’t you say, Patrina?

Patrina Nuske Small: Absolutely. And so much fun. And, in fact, the fun aspect was really the primary goal when we were sharing the opportunity to forum participants to take part. We wanted them to have fun, and we wanted them to actually be able to report on what they found, and how it tasted, and how it performed, and all of those exciting things. But we also gave them the opportunity to name any new variety that they discovered along the way. So they could name it after their pet, or their family members, or something else if they wanted to. And I chose to often use names that were associated with Australia, because I’m fairly keen that at least a small part of this project still retains its Australian background. The fun of naming something that’s really relevant to you, we felt, was a reward to people for al the hard work that they put in. And without our volunteers doing all of this work, this project would never really have gotten underway to the extent, or had the impact that it’s had, if it hadn’t been for our volunteers.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah. One interesting anecdote about naming is – one of our volunteers was from New Zealand, and he got essentially the Holy Grail. He ended up with a potato leaf dwarf with red and yellow bicolored swirled fruit that was absolutely delicious. And he named it W-H-E-R-O-K-O-W-H-A-I, which is a Maori term pronounced ‘fer-ti-kai’, for red and gold or red and yellow. And I sell lots of seedlings, and people look at it, and they don’t know how to spell it. I seem to be able to remember how to spell it because I’ve written it down thirty zillion times. So when you turn your team loose to name a variety, you have to be ready for anything to happen.

Patrina Nuske Small: That’s for sure.

Rachel Hultengren: So I would love to talk more about the community engagement aspect of this project, which makes it really unique. But first, Craig, you mentioned that there are a lot of benefits to growing dwarf varieties; people can grow them in smaller containers, they don’t require pruning, if you have just a small amount of space, you can grow something that maybe tastes still amazing, even though it’s much smaller. But why, given all that, why aren’t there more commercially-available dwarf varieties of tomato? Or rather, why weren’t there more before you started this project?

Craig LeHoullier: So this is an interesting one, and there’s a few reasons for it. The third catalyst for the project… So Patrina named one, where we could create this collaborative project and do crosses. I named a second, where we could fulfill the gardeners’ needs. But there’s a third catalyst, and that is, I was perusing old seed catalogues, and found a 1915 catalogue from a company called Isbell, that was in the Midwest in the United States. They described a tomato called ‘New Big Dwarf’ and they said, “We crossed the largest tomato we could find, ‘Ponderosa’, with a dwarf variety (and at this time there were only three or four of these around) ‘Dwarf Champion’. And ‘New Big Dwarf’ was the first, and up until our project the only, of the large fruited dwarfs. And I think it just went into the background, as more and more tomatoes came out, and then Burpee came out with ‘Big Boy’, and we get Big This and Better That and Ultra That and Super-Duper That. Gardening is very prone to trends and fads, and that which is advertised and that which shows up in seed catalogues. So again, this divine intervention aspect – for some reason, the whole dwarf category was just sitting there waiting to be plucked by Patrina and I to fill a gap that we felt was clearly needed. And now that we’ve filled it, if you look at a company like the Victory Seed Catalogue, where they can do star ratings to lots of our releases – people seem to love these things. My local customers are converting a lot of their garden choices from indeterminates to dwarf varieties.

There was actually a set of hybrid dwarfs on the market for a few years, called the ‘Husky’ series, but they never caught on because they were just kind of ordinary, red, typical type tomatoes. It took until the Seed Savers’ Exchange did their thing and made heirlooms known and then seed companies that specialized in non-hybrids made them widely available. Again, just the right time, it wasn’t until the 1980’s/1990’s/2000’s that the possibility of even creating the types of dwarfs we’ve created came about, because of the availability now of this amazing range of diverse heirloom varieties to take advantage of. That’s kind of my view. Patrina, I’d be interested in kind of your view of this as well – why now and why do they seem to be so well received?

Patrina Nuske Small: Well, I think that the populations are really moving towards city living and high rise living sometimes, and yet at the same time, people are becoming more and more concerned about their food and where it comes from. And they don’t really want to have food that’s either genetically modified or has tons of herbicides or pesticides or fungicides, etc. So people are being encouraged more and more to grow their own, so that they can get good flavor and and pick things when they’re actually ripe instead of having super market varieties that are picked so green that they almost never ripen. And people do care about what they’re eating these days and they haven’t got space, so it seemed to just make much more sense to offer them something that they could grow in pots on balconies. So yeah, I think it’s just a timing thing and serendipity and all of that in one.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah, and I think maybe this is a time to touch on another, what I think is a critical aspect of this project, that we were not doing this project for financial compensation. And, in fact, the end goal of this project is that once we have a great variety, we find a seed company that we deem worthwhile and give them a starter amount of seeds to actually put in packets and sell. And so another, I think, hallmark of our approach, is that this is an example of true altruism and humility and openness. That’s what I’m most proud of – what we’ve done, is that in this time, in this age, when we know how insane it is out there, we have not thought of doing any of this for any compensation whatsoever. Just the joy of gardening and the ability to give something wonderful.

Rachel Hultengren: So because there is no compensation coming back to the project, everyone, including yourselves, everyone that’s involved is a volunteer. Which, as you’ve said, this is the first all-volunteer tomato breeding project like it. And I’m curious, what has been the role of those volunteers as the project has gone forward? After Patrina did those crosses, then where did the seeds go, and what have been the roles of the other people who were involved?

Patrina Nuske Small: Right. Well, initially, after I made the initial crosses, I sent seeds to Craig to grow the hybrid generation, and then he also sent seeds back to me to grow the second generation, the F2. But he shared it amongst the team members that he had, and I shared the seeds that he sent me with my team members. And we went back and forward like this for quite a long time; however, the permissions for tomato seed, the permissions they sort of see-sawed here in Australia. Sometimes they were allowed and sometimes they weren’t, to be imported. And so that did affect the sharing process to some extent. But in 2013, the department here that controls all of that sort of thing got in touch with me, and I think they got in touch with Craig and people in the Northern Hemisphere too, that it was no longer possible to actually import tomato seeds into Australia unless you were willing to pay for the process of having them certified as being free of seven particular viroids they were concerned about here. And to do that you had to supply a huge sample of like 20,000 seeds or something for them to test. And this was not at all possible in our situation. So it more or less was at the stage, anyway, where we could just divide into two separate teams.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah – Rachel, you asked a great question. Because everyone is a volunteer, and because you’re going to get a wide variety of personalities, and many gardeners love to jump into something and then after a few years, “Been there, done that, now I’m ready to jump into something else”. Others have incredible persistence. Some take every little bit of data that’s available and share it with you, others it’s like pulling teeth even getting seed back from them. But if you think in terms of the fact that I’ve probably had 500 volunteers pass through my, I don’t know, guidance in the US in the years of the project, maybe 100 have been really really serious about it. And this isn’t to belittle at all the efforts of the other 400. Lives change, people’s focus changes, their interest changes, their ability to follow through… and it’s like everything else in life: “many are called, few are chosen” to become really obsessed with something. But the volunteers have all been wonderful, many of them have become friends.

It would be better if we could still share, because there are things that Patrina and I are working on, I’m sure, that we would just be dying to get into the other one’s hands. We enjoy watching what the other one are doing, but it’s not quite the same as when we could send little packets of seeds back and forth to each other.

Rachel Hultengren: How many varieties have been formally released through the project?

Craig LeHoullier: 106! And there are another 25 or 30 in Bill Minke’s hands. Bill is the fellow that lives in Wisconsin, long-time seed saver who grows out the seed to give to the companies. So if we were having this chat next year at this time, we could be to 130 to 135 released varieties.

Patrina Nuske Small: And all of them are released through the Open Source Seed Initiative, which is also amazing, that our volunteers all readily agreed to us being able to pledge them. And I think that’s astounding.

Rachel Hultengren: Why was it important to you as a community to pledge them as open-source?

Patrina Nuske Small: For a long time, really, I’ve been quite concerned about the way the food movement develops as corporations take more charge of our seeds. And it became quite a concern of mine, and when I came across the Open Source Seed Initiative, I thought, “This is amazing. This is wonderfully timely.” So I got in touch and started to do a little bit of pledging here and there. But in the end, we decided after discussions with Craig and discussions with Carol Deppe, we decided that perhaps it would be great if the whole project itself and all of the new varieties that they developed would be pledged as open-source seed. So we asked our volunteers, and sure enough they all agreed, and so there it is. All of them are OSSI pledged.

Craig LeHoullier: And I think, that is fantastic, Patrina. I love the way you put that. And on my part, I discovered the love of gardening just after I was married in 1981. And my grandfather actually instilled the love of gardening in me when I was three or four years old. It just took growing up, going to school, dating, all that stuff – it went dormant for a while. But when my wife and I met 40 years ago, the first thing we said is, “We need to have a garden.” And then I get bored with the ordinary, so I discover the Seed Savers’ Exchange in 1986. And then there is genealogy, and history, and stories. And your garden wasn’t just a bunch of plants or a bunch of red or yellow tomatoes. It was the story of the man, or the woman, or the family that sent you the seeds of those tomatoes. And the fact that they were freely shared, and the fact that they could be saved and freely reshared – before I knew about OSSI, that is my gardening principle, which is why I got so involved in the Seed Saver’s. It is very important to me that anything we can create will never be taken over by a corporate interest and profited, and people excluded from it. I think that they need to be there to be grown and enjoyed and shared and used forever. And that’s just extremely important to me.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Rachel Hultengren: We’re going to take a short break. We’ll get back to my conversation with Patrina and Craig in just a minute.

If you’re new to this podcast, consider listening to previous episodes from our first season. If you’d like to learn more about the Open Source Seed Initiative’s history and mission, check out season 1 episode 2, where I talk with Dr. Irwin Goldman and Dr. Claire Luby about intellectual property rights in crop plants.

After this episode, we’ll be taking a planned break from the podcast. If you’ve enjoyed listening, please consider filling out our listener survey at http://bit.ly/FreetheSeedsurvey. Knowing more about our listeners, what you’ve liked and what we could improve will help us as we consider creating more episodes in the future. Many thanks in advance for sharing your thoughts with us.

Now let’s get back to the conversation with Patrina and Craig. We discuss how, given the volunteer-driven nature of the project, there were limitations, but those didn’t preclude the project from experiencing success.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Rachel Hultengren: Going back to the logistics of running a program like this – when you would share seeds with your volunteers and they would grow tomatoes out, what sort of information were they sharing back with you about their observations of those plants, and were volunteers making the selections to say which plants with which characteristics would be saved or would be selected and continued in the process of stabilization? Or were they sharing information and then the decision of selection was a more collaborative conversation?

Craig LeHoullier: There are two aspects. First, we really wanted… because we were all amateurs, we wanted to impress upon people, “Let’s say if you grow six plants. Don’t pick tomatoes off all six of those plants and mix the seeds together.” So we needed to teach them a little bit that we’re doing single plant selections right now to carry on. So if you grow six plants, and you get a yellow and a red and a green and a purple and a brown and a white tomato, what Patrina and I would like back would be six packets of seeds; one from tomatoes from each of those plants. We delegated to the participants if something was wonderful. We did ask, initially anyway, for seeds of everything they grew out, and then took into consideration what they decided about the quality of what they found, and whether it was special enough to say, “This is the one of these six plants. These other five are interesting, but this one is the one.”

Now why did we ask for the other five back? Because we often found that the best results didn’t appear in the third generation. Maybe you’d grow a plant because it had interesting color, but it didn’t taste that good. And then in the fourth or the fifth generation, bingo. You found the one that had the color and the flavor associated with it.

But how would we have done this project if we were in a perfect world? We would have had acreage, from each cross we would have grown out 200 F2’s to see, as much as possible, what the possibilities are, and then we would have grown large populations from each of these. A lot of these were single or maybe double plant selections, meaning we had to get to what we wanted fairly quickly. But a least we’re growing out to enough generations to convince ourselves that we’re getting really good stability.

Patrina Nuske Small: We had sort of acknowledged right from the beginning that it was going to be a fun project, and that there were going to be limitations, and that we really wouldn’t be able to grow out these large numbers of plants for each generation that really, theoretically, one is supposed to grow in order to find the diamond in the bunch. So, knowing that we would have limitations, we still wanted to maintain it as being a fun and surprising outcome. And whatever we found, we found, and whatever we missed, we missed. And luckily, we just managed to find some beauties. So that made it even more exciting – the fact that even though maybe somebody only grew two plants, that one of them was absolutely great.

And I sometimes would pot up some of the non-dwarf seedlings and give them to family members to grow out, just to see what they got. Even though I only really grew dwarfs, I just wanted to check what else there might be, and in fact that’s how one of my favorite tomatoes came about, which is ‘Uluru Ochre’. It was actually a non-dwarf seedling that I gave to my brother to grow, and I went to collect samples from it, and I looked at this tomato, and I thought, “This is really an odd looking tomato. It’s a really strange color.” And it was a bit overripe when I felt it, and I thought it might be going bad. And I decided to still take it for seeds. But when I was processing it for seeds, it smelled great. And I thought, “Okay, well it smells alright, perhaps I’ll have a little taste.” So I had a little taste, and it was amazing – it just blew me away! It was a complex sort of flavor with a lot of sweetness, and I thought, “This tomato’s not bad! It’s the color that’s so strange about it.” And so of course I saved seed, but then I was thinking, “Gosh, I hope I can find dwarfs in the next generation (in the third generation).” But sure enough, we did find some dwarfs. From there we got ‘Uluru Ochre’.

Craig LeHoullier: And what’s amazing about that is Patrina discovered the first ever black orange. So a ‘Cherokee Purple’ and ‘Cherokee Chocolate’ are like black reds and black browns, black pinks. But ‘Uluru Ochre’ retains green as it turns orange and we’d bring that tomato to our ‘Tomatopalooza’ tasting events, and people would look at it and go, “Oh my gosh – am I supposed to eat that tomato?” I think it’s the most beautiful tomato in the garden, and others would probably have a little bit of compunction about, you know, “Do I go near this thing?” It is so unique! That was a brilliant find, Patrina, no doubt about it.

Patrina Nuske Small: Absolutely.

Rachel Hultengren: I look forward to seeing a photo of that. We’ll make sure to post it on the show-notes so that other people can see what that black orange looks like. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a tomato like that.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah. There’s one more point I wanted to make about data. So what we would have wished for everyone to do, and we couldn’t even fulfill this ourselves, would be plant height, plant habit, fruiting habit, apparent disease tolerance, yield per plant, days to maturity, blah blah blah. And sometimes what you’d get back from volunteers were “Here’s a picture of the tomato I grew and here’s the seeds. Oh, it was red.” Or, “Here’s a delicious tomato and here’s the seeds.” “Oh, by the way, do you remember the color?” “Oh, I kind of forgot.”

So what you had to do, and this is not a slam against anybody, because if I look back at my records over the past five years, I have got things missing that I would have sworn I would have taken down. You’re in summer time. It’s sweaty, you’re sweating all over your notebook. You’re busy, you’re trying to get things watered. You’re picking, you’re seed saving, you’re tasting, there just simply isn’t the time to collect and transfer all the data. So in our project, Patrina and I just made the best of what we got. And man, it was enough to get us to where we went to. (Laughs)

Patrina Nuske Small: Yeah, absolutely.

Rachel Hultengren: That’s a great thing to hear, because I’m sure that thinking that one needs to get all of the details of every potentially measurable trait – that might slow people down or make them more hesitant to start a breeding project. So to hear that you can be successful and come up with some really interesting and exciting new varieties even if you don’t take all of the notes that you possibly could take. Even if you just say, “You know, I really like this and I’m gonna save seed from it and put a star on the label,” and say, “Next year I’ll definitely grow it and look at it again.” Sometimes that’s all it takes.

Patrina Nuske Small: Yes. When I look at my notebooks from right at the beginning of the project, I hardly wrote down anything. I did have a notebook, but they are so disorganized, and I often just reported on the taste and color and that was it. But as I progressed through the project, and realized that there’s just so much more to observe, then each year I think my notebooks got better and better and better. And now when I look at it, I think, “Well, I didn’t even realize that I was actually developing, as I went, some good strategies here.” And I do encourage people to have a notebook every year, because you do forget. It’s easy to forget what you had on a certain year, and it’s really great when you need to look back. You’ve got it there; you’ve got the info of what you grew and how it performed.

Rachel Hultengren: It’s a really encouraging lesson, that you can get started on a breeding project, and it doesn’t have to be perfect. You can get better at it as you go. But just jumping in and getting started is a great way to learn about breeding, and… or, what’s that saying? A journey of a thousand miles starts with one step? That’s how breeding is, too.

Patrina Nuske Small: Yeah, exactly.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah, I wanted to raise a couple of just interesting surprises we’ve found along the way because they’ve led to some of our really great varieties, some of which have these wonderful Australian names. So Patrina crossed ‘Stump of the World’, which is a wonderful large pink heirloom, with this rather ordinary red dwarf, ‘Budai Torpe’. And you figure, “Okay, you cross a pink and a red – what are we going to get for possibilities out of this? We’re gonna get pinks and reds, and maybe they’ll taste good, maybe they won’t.” So the Sleepy family was born. Boom! All of the sudden, a purple tomato popped out of it. So you’re crossing a pink and a red, and somewhere hiding in one of those varieties were the recessive genes of the black tomato. And ‘Rosella Purple’ was born. And if you were to sit people down who have purchased our dwarfs, they would probably put ‘Rosella Purple’ in the top ten, and say, “That tomato is a challenger to ‘Cherokee Purple, in terms of quality and flavor.’” I mean, didn’t that blow you away, Patrina, to find purple coming out of that cross?

Patrina Nuske Small: It did, and that was such a surprise. And another surprise was in our cross Tipsy, which was a cross between ‘Golden Dwarf Champion’, which is a yellow tomato, and ‘Elbe’, which is an orange tomato, and the first generation – the hybrid generation – turned out to be red, and that was a surprise as well!

Craig LeHoullier: And some of the absolute best flavored tomatoes of our project came out of the Tipsy cross. So ‘Golden Dwarf Champion’, as an eating tomato, it’s from the 1880’s, it’s a Burpee variety, it’s one of the original dwarfs through the US tomato history. It’s okay – you grow it, you eat it, it’s like, “Yeah, it’s an okay tomato.” But when Patrina crossed it with ‘Green Giant’ and made the Sneezy family, and then crossed it with ‘Elbe’ to make the Tipsy family, almost everything that popped out of those crosses tastes spectacular. And that is something you can’t guess, you can’t plan for, and you can’t see. It’s just amazing to me.

Rachel Hultengren: So the Sneezy and Sleep families – you gave each cross a familial name, so that every line that came out of that cross kept that label of the family so that you could trace it all the way back to the cross that you made?

Patrina Nuske Small: Yes. The inspiration really came from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and we kind of stuck to the names in a similar fashion and made up names as we went along. Because if you’re trying to refer to a cross, you don’t want to have to write down each time “(’Golden Dwarf Champion’ X ‘Elbe’) F2 or F3 or F4”, etc. You can just write down “(Tipsy)F2, F3, F4”. It just made things so much more simple.

Rachel Hultengren: So we’ve heard from Patrina about her favorite variety that’s come out of this project. Craig, do you have a favorite variety?

Craig LeHoullier: Somehow I do. So Patrina did this marvelous cross, Sneezy, where she crossed ‘Green Giant’ onto ‘Golden Dwarf Champion’ in 2006. So the Sneezy hybrid was incredible. It was an eight and a half, nine out of ten flavor-wise, these big beautiful 8-10 oz. yellow tomatoes. So I thought, “Well, this is kind of hopeful.” And then the story goes to a fellow names David L., but he was affectionately known as Grub on Tomatoville. So Grub sent me some seed from something that he called ‘Summertime Gold 3’, and it was almost white. And I grew four of them. One of the potato-leaf plants had these gorgeous, 6-8 oz., variably-shaped fruit. But they were a nice, lovely medium yellow with a little bit of a red blush on the bottom. And the flavor was just supreme – it had everything I love in a tomato. It reminded me very much of the flavor of ‘Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom’ and also of ‘Green Giant’. And, you know, my wife, my best pal – I named it ‘Dwarf Sweet Sue’. We actually had someone who wrote editorials for the Raleigh newspaper who came over to taste tomatoes once. And he said he’d never tasted a tomato other than a red one. And he got to taste a slice of ‘Sweet Sue’ that day, and he thought it was the best tomato he’d ever eaten.

And we got it out to the F10 generation, and finally it was released in 2012 by the Heritage Seed Market. So Patrina made the cross in 2006, and it hit the market in 2012 at the F10 or beyond generation. So that showed the testament of our ability to squeeze two growing seasons into one calendar year by shuttling things back and forth between Australia and the US. And we got a full development of tomato done in about 5 years.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah, that makes a big difference, being able to have two generations in a calendar year – it speeds things up quite a lot.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah

Rachel Hultengren: So now that the project is winding down, what do you still feel is left undone? Now that these dwarves are out there – what would you like to discover about them?

Craig LeHoullier: What we don’t know is the relative disease tolerance of these, and what we don’t know is who really loves these and where are they doing well. So I would call it the regional adaptation of them. So we’ve got 106 of these dwarfs out there – which ones are going to thrive in the Pacific Northwest, or in New England, or in Australia, or in New Zealand? We had to focus on visual beauty and flavor, and if the two coincided (and I think they do on all of our releases); we didn’t want to put out anything beautiful that was tasteless. But what we don’t know is how well these are going to fight diseases that exist in various parts of the world or the country. So to me, that’s undone work, and I don’t know how to go about collecting that data, but I think that it’s important to know about. Have you ever thought about that, Patrina, how we understand how these things are going to do now that they’re born and they’re out there?

Patrina Nuske Small: Well, yes, I’ve often thought about it, and I don’t really have a good answer to that, but I’m hoping, as you’re hoping, that perhaps someone will be interested to actually assess some of the disease resistance aspects and perhaps, where necessary, breed that into the varieties that are tasting fabulous and where we don’t really want to lose a particular variety because of its uniqueness. That’s one thing. And secondly, I really try to encourage everyone to think about breeding more of the dwarfs by other sources that they can bring into the patch. Because to me, the more breeding that we do, the more chance we have of maintaining a really broad genetic diversity for the future. But part of that is also being able to get people to grow and continue growing them, because even if someone does some crosses and does bring in extra genetic diversity, but then somehow it’s not maintained or they don’t find enough growers or it just sits in a cupboard and never gets used – that doesn’t help the genetic diversity either. Yeah, I hope people breed; I want more people to breed. Have a go – have a go at it.

Rachel Hultengren: And if people are interested in, once they’ve looked at the catalogue of all of these 106 varieties that you’ve released, if they see one that they would like to use as a parent in their own dwarf variety breeding project, because they’re pledged as open-source, that’s something that they could do. They could ask for or purchase seeds from one of the companies that offers these varieties, and use them as a parent in a cross with their favorite heirloom, and then the progeny that come out of it, whatever variety they end up with – that is, according to the pledge, also open-source. So there’s the potential for many more dwarf varieties (or even indeterminates) to come out of the varieties that you’ve released and pledged.

Patrina Nuske Small: Yes. My concern is that I hope people will take it upon themselves to actually go to the effort of contacting the Open Source Seed Initiative in order to pledge the progeny. And I worry a little bit about that, whether or not everybody will continue to do that. But they should, because they have been pledged, and so the progeny are also meant to be pledged.

Rachel Hultengren: Patrina, you said that you hope that more people get involved and continue breeding to create more genetic diversity for the future. Would you have any advice for those aspiring tomato breeders?

Patrina Nuske Small: I think the main thing I would say to them is that if they’re interested in protecting the genetic biodiversity for their children and their grandchildren, that they should have a go at breeding. And these days, with the internet especially, I think that it’s a lot easier to get the information that you might need. And it’s not really all that hard to do. I found that it wasn’t at all hard to do, but I must admit that I have a very steady hand. And I didn’t break off many stigmas when I first started; I was quite gentle, and really had a very good success rate. But even if you do have some failures, and I certainly did have some failures where I did break the stigma or the cross didn’t work – it’s no big deal. You just do more of them. And, you know, I would just encourage everybody: have a go. Just have a go.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah. I had about a 25% success rate. So I tried 100 crosses one summer, and got 25 of them to take. And that is overwhelming in itself, because it means you get 25 families. Each one of those crosses sets you off on a research journey. So you could actually read about our dwarf project, and learn about basic tomato genetics, and if there’s a type of tomato that you don’t think is available, go for it! Take two parents that you think would create it, make the cross, get some people to help you out, grow it out, and odds are you’ll find what you’re looking for. It may be a needle in a haystack; it may be a 25% of 25% of 25% type deal, but if you grow out enough plants, you might find something wonderful. Roll up your sleeves, get out, pull your anthers off the flowers, get some pollen, and go forth and pollinate.

Patrina Nuske Small: And I could add something to that, too. If one of your parents is a dwarf and the other is not a dwarf, I recommend that you use the dwarf as a mother plant, and get the pollen from the other, non-dwarf, plant. Because the tomato that you grow on the dwarf plant, that you’re saving seeds from, that becomes your first generation. And when you grow those seeds, if there’s no dwarfs among them, you know very well that you were successful with your cross, because the first generation should not show up any dwarfs (the recessive trait); it should only show the dominant trait. And so you know that you’ve been successful, which is a bonus. It feels good.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah. Patrina has a Dwarf Project website, I have a website. I have some videos. We can really be kind of a resource in terms of email or whatever. Tap into my knowledge; I’m always happy to share things that I’ve learned with people freely. That’s kind of what it’s all about.

Patrina Nuske Small: Yeah, likewise here. We’re very happy to help people and to answer questions.

Rachel Hultengren: Wonderful. It’s really evident that you both have a really generous spirit, both in what you’ve just said, and the way that this project has been set up.

Patrina Nuske Small: Thank you.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah. Well, I’m inspired to get started breeding tomatoes. I’ve never done tomato breeding myself; I’ve worked in peppers and squash and a few other things, but I am already starting to think about the heirlooms that I would like to cross to some dwarf tomatoes, if you haven’t already done those. I’m hopeful that this will help inspire a lot of other people to jump into it also.

Patrina Nuske Small: That would be fantastic, honestly.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah.

Patrina Nuske Small: Awesome. And thank you so much for this opportunity. It’s such a wonderful opportunity, and I’m hopeful that people will really, you know, sort of take it from there, and keep going, and breed. Breed lots.

Rachel Hultengren: Craig and Patrina, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today. I’ve really enjoyed our conversation.

Patrina Nuske Small: Thanks, Rachel – it’s been great, and I’ve just loved the opportunity.

Craig LeHoullier: Yeah – absolute pleasure, Rachel, and nice talking to you, Patrina, and have a wonderful day everyone!

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Rachel Hultengren: I’ve been speaking today with Craig LeHoullier and Patrina Nuske Small about the collaborative, all-volunteer Dwarf Tomato Project. The Dwarf Tomato Project formally ended on December 31st, 2018, so activities are winding down, but if you’d like to grow any of the tomatoes that have come out of this project in your garden or use them parents for a breeding project of your own, you can find more information about those varieties (including where to purchase seeds) on the Dwarf Tomato Project’s website, at https://www.dwarftomatoproject.net/.

Craig also has a website, which we’ll link to in our show-notes, where you can read more about the Dwarf Tomato Project, learn more about Craig’s work, and find links to his books, Epic Tomatoes and Growing Vegetables in Straw Bales.

Be sure to check out our show-notes on the Open Source Seed Initiative’s website at http://www.osseeds.org for links and photos of ‘Uluru Ochre’ and ‘Dwarf Sweet Sue’. You can also download the full transcript of each episode there.

You can find and like the Open Source Seed Initiative on Facebook, and subscribe to Free the Seed! wherever you get your podcasts. Our theme music is by Lee Rosevere.

Thanks so much for listening! I’ve really enjoyed getting to make this podcast, and I hope that you’ve enjoyed hearing it. Until next time, I’m your host, Rachel Hultengren, and this has been Free the Seed!

The work that Patrina and Craig did was amazing. In Europe, I founded Kasveista, a small breeding company that aims to produce open-source seeds for vertical farming. We want to use soe of the varieties of the Dwarf Tomato Project to start our selection.