Episode two of the second season of Free the Seed! the Open Source Seed Initiative podcast

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 36:09 — 40.4MB) | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

This podcast is for anyone interested in the plants we eat – farmers, gardeners and food curious folks who want to dig deeper into where their food comes from. It’s about how new crop varieties make it into your seed catalogues and onto your tables. In each episode, we hear the story of a variety that has been pledged as open-source from the plant breeder that developed it.

In this episode, host Rachel Hultengren spoke with Joseph Lofthouse about his process of landrace breeding to develop varieties locally-adapted to the harsh conditions of his farm in northern Utah, and about the ‘Lofthouse-Oliverson Landrace Muskmelon’, a variety that came out of that breeding work.

Joseph Lofthouse

Joseph Lofthouse

Episode links

Find seeds of ‘Lofthouse-Oliverson Landrace Muskmelon’ on Joseph’s website.

Free the Seed! Listener Survey: http://bit.ly/FreetheSeedsurvey

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Free the Seed!

Transcript for S2E2: ‘Lofthouse-Oliverson Landrace Melon’

Rachel Hultengren: Welcome to episode two of the second season of Free the Seed!, the Open Source Seed Initiative podcast that tells the stories of new crop varieties and the plant breeders that develop them. I’m your host, Rachel Hultengren.

Every episode we invite a plant breeder to tell us about a crop variety that they’ve pledged to be open-source. My guest today is Joseph Lofthouse. Joseph farms in Northern Utah, where harsh growing conditions can make farming a challenge. We talk about how he has addressed this challenge through his plant breeding work, and Joseph describes ‘landrace breeding’, the process by which he develops genetically-diverse crop varieties that are particularly suited to his farm.

Rachel: Hi Joseph – welcome to Free the Seed!

Joseph Lofthouse: Hi! Thank you, Rachel and food-curious folks.

Rachel: So I’d like to start by painting a picture for listeners of your farm in Utah and the conditions there. Where in Utah are you, and what’s the weather like through the growing season?

Joseph: So I am in northern Utah, in Cache Valley, in a village called Paradise. And my growing conditions during the summer are desert conditions with intense sunlight in the daytime and intense radiant cooling at night. Super-low humidity, and I irrigate once a week.

Rachel: And how long have you been farming there?

Joseph: My family’s been growing in the same farm for 150 years, and I’ve been doing that my whole life as well, except for when I went away to the big city to work for a career, and then I came back home.

Rachel: I understand that when you came back home, you found that the conditions that you were growing in, it limited what you were able to grow. I’m curious – what did you try that at first just wasn’t successful?

Joseph: So a lot of crops, if I just buy something out of a seed catalogue, about half the varieties I buy that way will just plain old fail. And some things, like cantaloupe or watermelon, might be like 95% failures. Some things like turnips – any turnip that I plant is going to do well here. But the longer season crops, or the warmer weather crops, are hit-or-miss.

Rachel: What are the aspects of your growing area that are the hardest for crops to tolerate?

Joseph: Well, for warm- weather crops, it’s the radiant cooling at night. And for leafy greens, it’s the low humidity, because we might have 5% humidity in the evenings. And that leads to bitter lettuce and bitter spinach and bitter kale.

Rachel: How cold does it get, with that radiant cooling at night?

Joseph: We have about, sometimes, a 40 degree temperature change between the highs in the day and the lows at night. And the radiant cooling on the surface of the leaf, probably adds another- or subtracts another 10 degrees from that.

Rachel: So that can get pretty chilly for a warm-weather crop.

Joseph: Mmhmm. One of the tomato varieties that does really well for me folds its leaves up at night so that it doesn’t get exposed to intense radiant cooling so bad.

Rachel: Hm. Yeah, that’s interesting. So different crop varieties will have different traits that make them more or less susceptible to those harsh conditions.

Joseph: Mmhmm.

Rachel: When you came back from the big city and got started farming there, was there much seed production or plant breeding happening in the region?

Joseph: I don’t know of any seed production or plant breeding that’s happening in my valley, other than what I’m involved in. Mostly my community just gets a glitzy seed catalogue and buys a variety out of there. A lot of my community will buy varieties from humid climates, and then they get here and they don’t really do well with the low humidity, and so they burn up and they whine about not getting enough water, and things like that. And so, if I have any say to my neighbors about what catalogues they’re going to buy from, I really encourage them to find local sources of seed, to find locally-grown seed if they can, or at least regionally-grown seed, so that they start off with something that’s more suitable for our environment.

Rachel: So you took things into your own hands in a way, and started undertaking breeding projects that would develop those varieties that would do well in your valley.

Joseph: Yes, I did.

Rachel: Tell me about that decision.

Joseph: I was introduced to the idea of growing genetically-diverse crops, because I was looking for another sweet corn variety to grow. And I found a variety called ‘Astronomy Domine’, which had genetics from 200 varieties of sweet corn in it. And when I planted it in my garden, some of them grew little runty things, and some of them grew huge. And the tastes were fabulous, because there were purples and pinks and yellows and blues, and each of those has a different flavor. And I fell in love with that corn, and after a couple of years in my garden it became locally-adapted, because there was so much genetic diversity in it that there was lots of opportunities for finding things that really work well in my garden. So that set me on the idea that I need to grow genetically diverse crops and they need to be locally-adapted. And so I’m calling that, kind of, landrace gardening. And I’ve pretty much converted my whole farm to that type of growing.

Rachel: ‘Landrace’ is a term that’s often used to describe older varieties that were maintained on a farm, by a farmer, over many generations of the crop. How do you use that term?

Joseph: I use it in the same general pattern. I might often say the word ‘modern’ in front of it, so ‘modern landrace’ or ‘landrace development’ as in something that’s ongoing. In order for me to call something a landrace on my farm, it needs to be both genetically diverse and locally adapted.

So if I grow a bunch of varieties in a field and let them cross-pollinate, the first 2, 3, 4, 5 years I often call them a ‘grex’ meaning a mixture of varieties. But then somewhere along the line they just start growing really well for my farm. They please me as a farmer, they please my community, they’ve become part of our social fabric and they integrate really well with the soil and the bugs. And that’s when I start calling them a ‘landrace’ – when they’re really part of me and part of my farm.

Rachel: What do you do every year, after you’ve sown all these seeds out in the field? What do you do next? What’s the general process of landrace breeding?

Joseph: So the very fundamental … that underlies everything else, is: a plant has to produce seeds in my garden, under my growing conditions and my habits. And if it doesn’t produce seeds or throw pollen into the patch, then it pretty much dies out. And so landrace plant breeding is very much survival-of-the-fittest, at its very fundamental level.

For example, when I order spinach varieties out of a seed catalogue, about 50% of them will be two inches tall and go to seed. And the other half of them will be big, huge plants that flower much later. And so it’s really easy to know which ones are suited to my farm and which ones aren’t. And so the little rinky-dink plants I just pull out. And they don’t ever contribute to the genetics of my farm.

Rachel: So it’s a continuous process of Nature winnowing down the population you have out in the field, so that you end up with only individuals that survive by being well adapted to your farm. And then those are the individuals that contribute seeds or pollen to the next generation.

Joseph: Yes, that’s right. And I’m also continuously introducing new varieties. People will send me gifts, or I’ll get something from the seed rack or whatever. And I’ll plant that 5%, 10% next to my landraces, and it might contribute pollen or seeds or it might not. But in that way, I’m continually introducing new genetics as well as maintaining the old.

Rachel: How many different varieties do you generally start with when you begin a landrace breeding project?

Joseph: It depends. I like 2 or 3 or 4 or 5. Another way I have sometimes started a landrace breeding project is with accidental cross-pollinations that happened in my garden. So in that case, there would be, say, two varieties that were the parents of the landrace.

Rachel: Why is it important to start with a lot of genetic diversity when you’re trying to adapt a crop to your specific location?

Joseph: In order to select for traits, the variety has to have those traits inherently inside of it. And if I start with a highly inbred crop, I’ll end up with a highly inbred crop. But if I start breeding with a crop that has lots of genetic diversity, then there’s much more opportunities for the genetics to get rearranged so I can find what I’m looking for.

Rachel: How many individual plants do you try to have out in a field when you’re working on developing a new landrace variety?

Joseph: Well, I grow about an acre and a half of annual vegetables. And so it’s really easy for me to throw a lot of plants into a field, and I might grow 5,000 corn plants and a thousand squash plants, kind of thing. But you certainly don’t need those kind of numbers for smaller breeding projects or seed saving efforts. And it depends a lot on the crop, too. Some of the outcrossing crops like larger populations, where some of the inbreeding crops, it don’t matter so much.

Rachel: Mmhmm. On your farm, why is to helpful to have so many plants of a given crop?

Joseph: Well, partly I’m feeding myself and my community. And while I’m doing that I might as well grow seed, or while I’m growing seed I might as well feed my community. However you want to look at that. So larger numbers are easy for me.

Rachel: Yeah, that makes sense. And you can maintain more genetic diversity if you grow large populations; I want to talk more about that in a minute, but first let’s talk about your general approach to plant breeding – do you have a vision for the end result when you start a project

Joseph: Sometimes I have a vision of a goal, and sometimes the goal is just as simple as, “I want to harvest a melon in my garden.”

Rachel: Mmmhmm. I’ve read on your website that you describe landrace breeding as a combination of survival-of-the-fittest and farmer-directed selection. Why are both of those important?

Joseph: Well, because if I don’t do any selection as a farmer, it seems like the population isn’t progressing and developing, it’s just sort of staying stagnant. And part of being a landrace is becoming part of the community, and so when I select for tastes that are really pleasing to me, they tend to be really pleasing to my community. So I think, you know, that those two, the natural selection and the farmer selection, have to go hand in hand to make the variety truly locally-adapted.

Rachel: So if you took only the fittest, you might not have something in the end that fits the tastes of your community or the demands of your consumer, and if you selected for the prettiest or the tastiest, you might not end up with something that’s very robust.

Joseph: Right.

Rachel: I’d like to go back to the image of a field with many different varieties growing in it, and cross-pollinating as the starting population for your landrace breeding. So every year, the most fit survive. Do you evaluate all of those individuals that have survived to produce seed for their quality traits? Do you taste all of those, or do you go and look at the color or other qualities of each of those individuals and do a selection every year?

Joseph: Yes. My strategy is to taste every fruit before I save seeds from it. And if it’s a crop like tomatoes that I don’t really like –

Rachel: You don’t like tomatoes?

Joseph: No, they’re nasty little things. (Laughs)

Rachel: But you grow them.

Joseph: But I grow them. And lettuce, I taste every lettuce for bitterness. And the first time I did that, I got sick, sick, sick. That was before I learned that I need to spit out instead of swallowing the juice. And because I taste every fruit in every generation, it quickly becomes that the fruit get really pleasing to my taste buds really quickly.

Rachel: So you start with a lot of genetic diversity in the field, which hopefully ensures that there are at least some individuals that will survive and that you can select. And you’ve said that you try to maintain quite a lot of genetic diversity in the landraces you develop.

Joseph: Yes.

Rachel: What are the effects of having really high genetic diversity in a given field of plants?

Joseph: One thing that happens is that a total crop failure becomes very rare, because some families or other in the population tend to do well whether the year is extra hot or extra cold or extra wet or whatever. Some family type will tend to produce a crop. So that tends to lead to a more stable, consistent harvest.

Rachel: But then are there… is there a lack of uniformity in other traits that might be important to harvest or cultivation?

Joseph: So I select for uniformity in the traits that matter to me. For example, on squashes, they always have to taste good. They always have to produce a harvest for me. On squashes also, I like fruits that are approximately 10 lb fruits. So if anything turns out fifty pounds, it’s going to be culled; if itturns out one pound it’s gonna get culled. So I end up with some traits that are consistent and stable, and some traits that I let float. Because on my squash I don’t care what the shape of the leaf is, and I don’t care very much about what the shape of the fruit is. It could be a round pumpkin or a long-necked butternut, and it still has the same taste and uses in the kitchen as any other butternut.

Rachel: So the strategy of selecting for the traits that are of high importance to you, but not selecting on traits that aren’t as important, maintains a higher level of genetic diversity. And the hope is then that that genetic diversity will give resilience to the population in the face of things like diseases or pests or short- or long-term climatic changes.

Joseph: Right. Because a lot of those internal traits I can’t see with my eyes, but if I select for diversity in the traits that I can see, then maybe I’m also selecting for diversity in traits that I can’t.

Rachel: How many varieties have you developed this way?

Joseph: So I’m currently working on, or finished, or however you want to say it, about a hundred species.

Rachel: Would you say they’re finished?

Joseph: Well, they’re never really finished. But some things, like my moschata* squash, I’m pretty content with right how it is and don’t have any goals to make it different, other than my chefs are asking for a different shape in the butternuts. So I pulled those with that shape out of the population and I’ll grow those in a separate field next year, and maybe get a shape that my chefs want more.

Rachel: But otherwise, you maintain one landrace variety per species that you grow?

Joseph: That’s my general strategy. Perhaps two or three per species. For example, on the pepo** squashes, I’m working on an acorn squash mix and also a zucchini. And I’m keeping those totally separate. And on corn, for example, I have a flour corn, a flint corn, a sweet corn and a popcorn. And I keep each of those separate.

Rachel: So you maintain those fields at distances that isolate the population so that they can’t be crossed together, so that you can maintain a flour corn separate from a flint corn, and the summer squash separate from the acorn squash?

Joseph: Yes. I have six fields, so I can keep them separate. And on the corn I also have the ability to stagger the flowering dates so that I can grow several varieties in the same field. But when I’m growing landrace style, I don’t have to worry as much about isolation as, say, a commercial farm does that’s providing seed for an entire country. And most of the charts that we see are designed with the seed company needs in mind, and not the needs of the backyard seed saver.

Rachel: So you’re not supplying seeds of these landraces across the country, but do you share seeds of these landraces with your neighbors that have farms?

Joseph: Well, I share the seeds widely, but I’m sharing them with the understanding that they’re going to be genetically diverse, and there’s going to be surprises in what comes out, and so I’m not trying to provide people with a uniform, consistent variety.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Rachel: We’re going to take a short break; when we come back, Joseph and I discuss the process of developing ‘Lofthouse-Oliverson Landrace Muskmelon’.

Thanks to everyone who has taken the time to share their thoughts through our listener survey. If you’d like to tell us what you think of the show, you can do so at http://bit.ly/FreetheSeedsurvey.

Are you friends with farmers, gardeners, or anyone who’s interested in where their food comes from? If you’ve enjoyed listening to this episode or any other episode of Free the Seed!, consider telling a friend about this podcast.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Rachel: Let’s get to the focus variety of the episode, which is the ‘Lofthouse-Oliverson Landrace Melon’. Describe the melon for us: what do you highlight when you tell people about it?

Joseph: So the melon is a cantaloupe, or the same species as a cantaloupe. But if you go to the grocery store and you buy a cantaloupe, it’s going to not have very much sugar, it’s not going to have very much smell, and it’s just going to be a bland, hard, barely-palatable thing pretending to be food. (Laughs). If you buy one of my muskmelons at the farmers’ market, it’s going to be super sweet, it’s going to be tender and juicy and it’s going to have an aroma that you can smell as soon as you come into market. Not really even the same product as what you buy in a grocery store that they call a ‘cantaloupe’.

Rachel: Part of that is how far cantaloupes generally travel from a farm to our grocery store, because fruit is often picked pretty underripe so that it can withstand the transportation process of getting to the grocery store. But it might also be true that the varieties that travel well aren’t the tastiest melons to start with. Is that right?

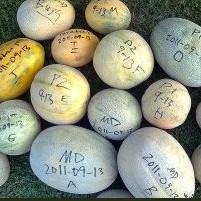

Joseph: Right. About ten years ago, I started growing cantaloupe, and they just wouldn’t grow in my garden. And so I decided I was going to start a cantaloupe breeding project. And so I collected, the first year, about 30 varieties of cantaloupe, and planted them all together in my garden. And probably about 75% of them died as young plants. The bugs ate them, or they didn’t thrive in the soil, or whatever. And a few of them produced a few fruits that were still green when they got frozen. But I went ahead and saved seeds from them, replanted those the next year, gathered together another 25 or 30 varieties, planted them all together in the field. Most of them died. But there were a couple of plants that produced more fruit than all of the rest of the patch combined. And these are patches containing a couple hundred plants. And so then the third year, saved the seeds and replanted, and I was harvesting bushels upon bushels of cantaloupes, and they were actually ripe and mature. And so that was the beginning of my landrace cantaloupes.

And then I started tasting fruits. Because the first thing I have to have is something has to reproduce and make seeds in my garden before I can select for any other trait. And so I started selecting for taste, and after a couple of years I couldn’t call them ‘cantaloupes’ anymore. I had to start calling them muskmelons, because they were so delightful and so smelly and so pleasing to me as a primate. And since that time, I’ve more or less just been maintaining the population. Once in a while I might trial a new variety next to it, just to see if there’s anything else that I want to add to the population.

Rachel: So you spent a few years growing all of the cantaloupe varieties you were able to get seed of, and saved seed from the few survivors. Then after you ended up with a population that was all surviving and producing fruit and seed by the end of the season, you were able to go through to select only the plants that produced the fruit that was most appealing to you, and save seed from that subset of the population.

Joseph: Yes. And one of the nicest compliments I ever received about my seed saving is one of my neighbors said, “Thank you. This is the first time I’ve ever been able to grow a cantaloupe in this valley.” And that is a really nice thing to hear (laughs).

Rachel: Yeah, absolutely. Are there other crops where you’ve had that sort of impact through your breeding?

Joseph: The squashes have been another one where that was really successful for me. Because when I buy them from the seed catalogues, there’s all kinds of failures. On the topic of the muskmelons, I wanted to mention where the name “Oliverson” come from. There was another farmer in my valley, she lives about 30 miles away, and her and I were doing the same sort of seed saving at the same time and then we were swapping seeds back and forth. And so that’s why Susan’s name and I name are both on the variety. Because we played similar roles in developing it.

Rachel: In an earlier episode of this show, I spoke with Dr. Deppe about developing a new variety of summer squash, and she described the process of hand pollinating individual plants. It sounds like that’s not something you had to do in the process of developing this variety, but could you describe melon flowers for our listeners?

Joseph: So melon flowers have a male flower and a female flower on the same plant. And the female flower has a little fruit underneath the blossom, and the male flowers just have a stem. And so cross pollinating them would mean taking the pollen and putting it on the mothers you wanted. In my own work I generally choose promiscuous pollination because I might not know who’s the daddy, but if I have good mamas and good daddies I’ll tend to get good offspring.

Rachel: So you’re able to select for the good mother plants by evaluating fruit that they produce and then saving seed from that, and hoping that they are also contributing pollen to the population?

Joseph: Yes. I do have the ability sometimes with some species to go through the patch and cull before fruits are made. Like on squash, I could go through the patch (before) the first flush of fruits appear, and cull all the plants I didn’t like, and cull all the current fruits. And then let them create fruits next time, or for a second flush, with parents that I felt better about.

Rachel: So that speeds the process up of this breeding project, by eliminating individuals that you don’t want contributing to the next generation’s genetics.

Joseph: Right. Uh-huh. And, for example, watermelons – when I first started growing them, there were some that had hard seeds, which meant that they would germinate like a month after the rest of the patch had germinated. And that trait was easy to eliminate, because I’d just go through the patch and watch for those late-germinating plants and chop them out. And so I was able to eliminate that trait in just one or two generations.

Rachel: You mention that you’ve worked on over a hundred different species, doing this landrace breeding. How is breeding melon different from breeding other crops?

Joseph: Well, there’s two basic reproductive strategies in plants. And one would be the inbreeders, they would be things like beans and peas and domestic tomatoes. And then there’s the outcrossers, which would be things like the broccoli and cabbage and corn. And the outcrossing species tend to really adapt quickly to a new garden, where the inbreeding species don’t change much, and so you might… can eliminate plants that aren’t very locally-adapted, but it’s just slower.

Rachel: Because self-pollinating or inbreeding species tend to set fruit before having the opportunity of being pollinated by other plants, you don’t have as many opportunities for the genetics of the different individuals in the population to get mixed up to then be able to select a new combination of genetics out of that population that might be better suited to the location where you are. Whereas outcrossing species or cross-pollinated species, their very nature is that they pollinate one another easily because of their flowering structures or their ability to bring pollinators in, and that provides you with the raw material of these new combinations of genetics every time.

Joseph: Yes, exactly. So when I’m playing the genetic lottery, the wheel is spinning much faster on the outbreeding species than on the inbreeding. And one way I try to overcome that is, for example, with my beans, I pay a lot of attention to finding the rare naturally occurring hybrids. Because if I can find those hybrids and identify them and get them into a place where I can keep track of them a little bit, then that gives me a lot more opportunities to select for local adaptation.

Rachel: How important are locally-focused breeding efforts like the ones you’ve been describing?

Joseph: Well, for me, because of my difficult climate, they’re super important in a lot of species. Turnips, I don’t care – any turnip I plant is going to grow well. But other varieties, the local adaptation’s really important to me. Because I have three or four traits that are sort of just on the margins of where plants can actually grow good. My soil tends to be clay-ish and alkaline, and it’s really arid here, and the super high UV – all of those are sort of marginal growing conditions to start with. So it’s really helpful if I can grow varieties that do fine with those kinds of conditions.

Rachel: Why did you pledge this population to the Open Source Seed Initiative?

Joseph: Because Carol Deppe asked me to.

Rachel: What was her argument?

Joseph: That it would prevent pirate-y corporations from stealing it from me.

Rachel: Was that a concern that you had?

Joseph: No, but I really admire Carol, and like to cooperate with her where I can.

Rachel: You’re also the moderator of the Open Source Plant Breeding Forum. What’s the purpose of that online space?

Joseph: The Open Source Seed Initiative wanted to have some place where people could discuss plant breeding, so they funded the creation of that forum. The forum provides both education about plant breeding and opportunities for people to collaborate on breeding projects.

Rachel: Do you have any advice for someone who might be considering starting a plant breeding project themselves?

Joseph: Well, one thing I like to say is that if someone is saving seeds, they’re basically already a plant breeder, because the mere fact of saving seeds means that we’re doing a little bit of inadvertent selection, even if we’re not doing conscious selection.

Rachel: How would you encourage someone to think about which seeds to save?

Joseph: Well, some plants are just easy to save seeds from. Like beans, for example. They’re big plants, they’re big seeds, they’re easy to handle. So they’d be a good species to start saving seeds from.

Rachel: If somebody who was growing in, not your valley in Utah, but somewhere else that was also a harsh set of conditions, if they wanted to start a landrace breeding project, how would you describe how they would go about doing that well?

Joseph: So what I would recommend is finding varieties that already are known to do well in that area, and growing those together and allowing them to promiscuously cross-pollinate as much they’re able to do, and then use that as the foundation of their new variety.

Rachel: Is there anything else you would say to a potential future landrace breeder?

Joseph: You don’t need to fear diversity, because it’s the strength of a landrace. I know a lot of people are interested in heirloom preservation, and my strategy for preserving heirlooms is to let them intermarry with other heirlooms. So I’m not saving a particular arrangement of DNA, I’m just saving the family in general.

Rachel: Joseph, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today about your breeding projects, and about this muskmelon.

Joseph: Oh, you’re welcome Rachel, and it was a pleasure talking to you.

Rachel: Check out the show-notes for this episode at https://osseeds.org. That’s also where you can find all the past episodes of this show, along with show-notes and the transcript for each episode.

Joseph Lofthouse sells seeds of the varieties he maintains on his website – http://garden.lofthouse.com/ – you can find his full seed list there.

The Open Source Plant Breeding Forum, of which Joseph is the moderator, is an online space that provides both education about plant breeding and opportunities for people to collaborate on breeding projects, and anyone can join for free at http://opensourceplantbreeding.org/.

Our theme music is by Lee Rosevere.

Thanks for joining us! Until next time, I’m your host, Rachel Hultengren and this has been Free the Seed!

——————————————————————————————————————————————

* Squash in the species Cucurbita moschata, which includes butternut squash and Long Island Cheese, Pumpkin among others.

** Squash in the species Cucurbita pepo, which includes both summer squash cultivars (e.g. zucchini types) and winter squash cultivars (i.e. acorn, delicata and sweet dumpling types).