Combining Cucurbits for Downy Mildew Resistance and More

Wednesday, May 11th, 2022

An Open Source Seed Initiative webinar

Presenters:

Michael Mazourek (Cornell University)

Edmund Frost (Common Wealth Seed Growers)

Moderator: Rachel Hultengren

———————————————————————————————————-

Speakers’ bios

Michael Mazourek

Michael Mazourek is the Calvin Knoyes Keeney Associate Professor of Vegetable Breeding at Cornell University. Michael is a breeder of peas, beans, squash, cucumbers and peppers and has released numerous cultivars and breeding materials that are shared by small, regional seed companies. Michael shares the craft of plant breeding with students at Cornell, through grower conferences and field days. Michael is a pro-bono co-founder of Row 7 Seeds which is helping public and freelance plant breeders share their creations with a public that seeks choice and diversity in their food.

Edmund Frost

Edmund Frost has been growing vegetable seed crops in Virginia since 2007. In the past several years he has become increasingly involved in research, breeding and selection work, especially focused on Cucurbit crops, and on resistance to Cucurbit Downy Mildew. In 2014 he helped start Common Wealth Seed Growers, a farm-based seed company and cooperative of several seed growers from Virginia and Tennessee. See commonwealthseeds.com/research for more about the work Edmund and Common Wealth Seed Growers are doing to identify and develop regionally suited and regionally adapted varieties.

Publications referenced during the webinar (in order of appearance)

Cavatorta, J., Moriarty, G., Henning, M., Glos, M., Kreitinger, M., Munger, H. M., & Jahn, M. (2007). ‘Marketmore 97’: A Monoecious Slicing Cucumber Inbred with Multiple Disease and Insect Resistances, HortScience horts, 42(3), 707-709. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://journals.ashs.org/hortsci/view/journals/hortsci/42/3/article-p707.xml

Brzozowski, L., Holdsworth, W. L., & Mazourek, M. (2016). ‘DMR-NY401’: A New Downy Mildew–resistant Slicing Cucumber, HortScience, 51(10), 1294-1296. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://journals.ashs.org/hortsci/view/journals/hortsci/51/10/article-p1294.xml

Holdsworth, W. L., Summers, C. F., Glos, M., Smart, C. D., & Mazourek, M. (2014). Development of Downy Mildew-resistant Cucumbers for Late-season Production in the Northeastern United States, HortScience horts, 49(1), 10-17. Retrieved May 16, 2022, from https://journals.ashs.org/hortsci/view/journals/hortsci/49/1/article-p10.xml

——————————————————————————

Carol Deppe

Hello, friends. I’m Carol Deppe. I’m Chair of the Board of Directors of the Open Source Seed Initiative. On behalf of the OSSI board, I welcome you to our second webinar. OSSI, as we call, it is an organization that is fighting for the rights of farmers, gardeners, and plant breeders everywhere to have full access and rights to the seed we need: rights to plant, grow, save seed, share, sell, breed with it, and use it however we want. We do this by working directly with plant breeders who pledge one or more new varieties they have created into our program. Thereafter, seed of their variety is distributed through cooperating seed companies with the OSSI pledge, which says, “You have the freedom to use these OSSI-pledged seeds in any way you choose. In return, you pledge not to restrict others’ use of these seeds or their derivatives, by patents or other means, and to include this pledge with any transfer of these seeds or their derivatives.” There are now more than 500 OSSI-pledged varieties being sold by more than 70 OSSI-associated partner seed companies. For more information about OSSI or these varieties, check out our website at osseeds.org. Today’s webinar is “Combining Cucurbits for (Downy) Mildew Resistance and More,” the conversation between Michael Mazourek and Edmund Frost, representing one of the few collaborators between the univer- university plant breeder and an independent farmer breeder, each bringing their own unique perspective to their work. Their work is on disease resistance and local adaptation in cucurbits. It often involves wide crosses, rare in the mainstream plant breeding world. Michael Mazourek is on the vegetable breeding faculty at Cornell, where he breeds peas, beans, squash, cucumbers and peppers. He is also a pro-bono co-founder of Row Seven Seeds. Edmond Frost is freelance plant breeder and vegetable seed grower in Virginia. His work focuses on cucurbit crops and downy mildew resistance. He is also a co-founder of Common Wealth Seed Growers. For more on the work of Michael and Edmund, or on Row Seven Seeds or Common Wealth Seed Growers, check out the links in the program notes. I’ll now turn these proceedings over to our intrepid moderator, Rachel Hultengren.

Rachel Hultengren

Thanks, Carol. We’ll be hearing a 45 minute presentation from Michael and Edmund. And then we’ll have about 45 minutes for questions and answers. So I’ll ask that folks hold their questions until we get to the Q&A. Although if you have any questions that you’d like to share in the chat, I can keep track of those and then make sure that they get brought up at the end of the presentation. So Michael, and Edmund, over to you.

Michael Mazourek

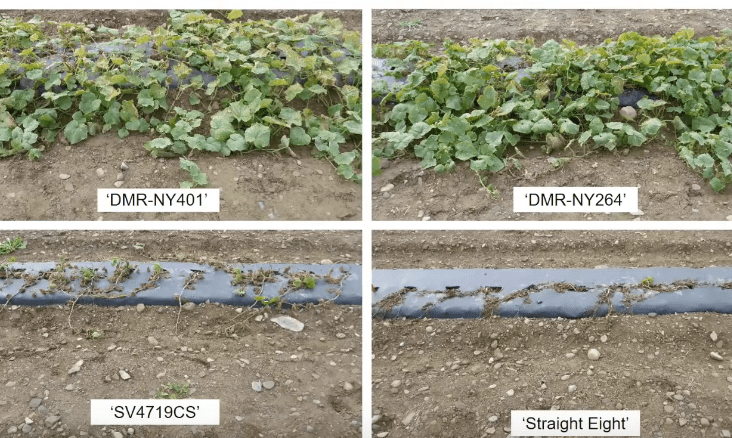

Thanks, Rachel. It’s, it’s cool to be able to chat with you all this afternoon or this evening or wherever time it is where you’re at. So Edmund, and I, we’re gonna talk back and forth. We have a couple of different stories to weave together. And then you know, what, I really look forward to chatting with you all in the Q&A. We’re going to touch on some of the things that excite about cucurbits but there is, there’s oh so much more we can, to talk about. We like talking about cucurbits, let’s just put it that way. Right. So the one of the first things I want to talk about is downy mildew resistance in cucurbits. This is how Edmund and I first connected, I believe, and started evolving collaboration. But, so, there’s a lot of downy mildews – the basil downy mildew, hops downy mildew, sunflower downy mildew, like everything has its own downy mildew. They’re these oomycete pathogens, which is like a fungus but a little different in how they can sexually reproduce and evolve. And while we had great downy mildew, downy mildew resistance in cucumber for decades as part of some older breeding efforts, when there was a resistance breaking strain of downy mildew, it had nothing to hold us back. It was not so really known anymore to plant pathologists, to plant breeders, to extension, all the diagnostic people – this was something that… they… was kind of out-of-sight, out-of-mind for decades. So when it popped up back in the US, on the East Coast, about 2004, 2005, that really was devastating to the industry. It over, it overwinters in Florida, move up the East Coast, every, every summer as plantings move further north. Also there seems to be an epicenter around the Michigan/Ontario era, area, that moves in. It’s also global, it’s wherever it’s kind of humid and they’re growing cucurbits, cucumbers especially, it just takes off. So there was a big scramble. There’s lots of scientific articles about people reacting to this. What is this? What do we do? What, how does this help us learn about how to deal with future plant pandemics, right? The symptoms on cucumber are pretty easy to recognize with… and pretty much any place humid, globally – they grow cucumbers, you’ll see this. It has this patchwork quilt appearance where these polygons of yellow and brown is really diagnostic. And it tends to, unchecked, just will rip through a field. So here’s a trial in North Carolina with great collaborators down there in the photo credit. But, so, what you’re seeing, if you’re on the audio version, is: there’s some plants there’s going to get some mild symptoms in the leaves. And then there’s like 10 days later, they are wrecked, it is just brown and crispy, the plants are gone. So it really does a number. And so the spores land, they’ll go through their life cycles, they have alternating wet and dry and then they’re airborne and are blown to the next field. And so that airborne dispersal, combined with the sexual mating approach for them to evolve and share genes makes it really something to contend with. You know, at the least it’s, it doesn’t overwinter really. And it is restricted by the crop type. So, for me, this was like one of the challenges when I first joined the faculty a couple years later, and I was tasked with trying to figure out how to do this. At the time, I was the second-to-last public sector cucumber breeder left. I am currently the last public sector cucumber breeder left, I know of, that’s really focused there on the plant breeding. So, you know, that’s, it’s like, well, we’re able to do some things to help. But my goodness, there’s almost no one to do anything on the public sector side. Nod to OSSI-related comments later on there. But so I tend to be able to make some really fast progress in plant breeding. But I want to unpack that a little. I haven’t, I usually don’t unpack that much, right. And so one of those reasons is that I am part of this legacy of seed being saved and archived at Cornell. So I am able to do some, some things a little faster than, than some in the, in some of the breeding spaces. But I’m able to do that, because I have this fantastic set of germplasm to work with and publications that give me the roadmaps of what people did. So we knew Henry Munger, Molly Jahn, etc, had left behind the ‘Marketmore 97’ cucumber that was the pinnacle of disease resistance, at, well, as of 1997. It was when they were breeding for downy mildew resistance. So, or with those genetics in the background, even though it wasn’t a big problem, and so I was able to start working with that and we were looking for what to combine it with. Michael Glos, a farmer-breeder in the program, was able to give me a great tip that there’s this hybrid in Cook’s Garden – ‘Ivory Queen’ – that was this white pickling cucumber. It was not normal to a lot of people. But there was some growers that found it was giving them some degree of protection with resistance. So we combined these two modern sources of resistance where the backgrounds were who knows? Well, ‘Marketmore 97’ we do, ‘Ivory Queen’ we still don’t quite. And we put these populations out in the field. There’s a lot of ways you can work for breeding for disease resistance with a lot of ratings, a lot of data collection. My mind doesn’t work that way. We walk the fields at the end of the season, and just look for the survivors. So here’s a field of cucumbers where they’re all wrecked with downy mildew, some are just dead and done. Some are struggling and holding on. Some have, one indicator has got a pink flag in it and it’s still alive and trucking at the end of the season, it goes right up until frost for us. So this was part of our idea of ‘how can we help the plants evolve like the pathogen is evolving? Right? So that’s one of the problems with a lot of cultivars, and how we keep them as varieties in stasis – is that the world around us, climate or ecology, or people or cultivation methods or, like everything’s still changing. So how can we help set up a system for varieties to evolve? Right, so a lot of you are probably interested in open-pollinated cultivars and their capacity for that. We were taking kind of an accelerated approach toward that with our greenhouse. So I just go at the end of the season. What plant makes good cucumbers, what plant is still alive and producing? We take cuttings of those, because we don’t want pollen from all the dead plants mixed in. Cucumbers root so well. So we just take a cutting, put it in a pot of wet soil. We used to do, just put like a bag over the top – a clear bag. They root within a couple of weeks, and then you’re off and going, survival of the fittest for the next generation process in the greenhouse. We have a better method now. I had an undergraduate student that, I didn’t describe this well enough, so she did this approach her way, and took these long, like 18 inch, two foot long cucumber whips from the ends of the plant. I was like, “Oh, gosh”, and we just put them in these big, like Tupperware, clear plastic boxes instead of these bags they wouldn’t fit. They almost all took so we have like a 50% take rate, kind of depends if it’s getting cool at the end of the year. She had like a 100% take rate. We’re thinking is because of these long whips she had, maybe it’s because the apical meristem that has all its hormones was very far separated from the zone we wanted to root. So perhaps that was what was doing it. But so anyway, so the idea here is it’s very much a evolutionary, survival of the fittest, the survivors are what’s intermating. And we’re intermating to continue driving the population forward. And we can talk more about that. But actually, the expert in a lot of the other ways to do it is Edmund, and I don’t want to take into his time. A very humble, uh, world expert on downy mildew resistance breeding in cucurbits. He will tell you otherwise, but I’m here to give my two cents there. So, but, so one of the things here is we have two, I’m showing two panels of, on the top here, two cucumber varieties that are super resistant, one more than the other. So there’s ‘DMR-264’, and ‘DMR-401’. It’s the breeding lines, it’s the plots when we first recognized them as having potential. You can see they have potential, I hope, here, if you compare them at the bottom two panels, so one is ‘Straight Eight’, where you see a couple of little brown wisps, where the plants were and when downy mildew moved in and they are gone now. Also you see a variety that was labeled as resistant at the time. It is not much better than the susceptible control, right? So a couple things about these two varieties. They were developed with graduate students, Bill Holdsworth was the lead and Lauren Brzozowski was the lead. We’ve, they’ve taken it further into pickling cucumbers, etc. But these were varieties we released really quickly. They weren’t the best we could do, they weren’t…. We continue to make improvements really iteratively. Some people ask, “When do you know when it right is finished?” Some people say it’s never finished. I will say, “As soon as you can share it with someone that needs it.” So luckily, I had a way to share these very quickly with the public through Edmund’s seed distribution efforts. And so first ‘DMR-264’, then a couple of years later, ‘DMR-401’. And we have a couple other new generations that should be out in the world in a year, maybe two. So that’ll be a way to continue, continually sharing with growers, immediately, the best of what we have to offer. And I think that’s really important for how I approach what I do and how I do is – I want it to be of benefit to people and even if it’s… if it could use more years of trialing, if they’re desperate to grow a crop, why not let them be doing the trialing as they grow? Don’t plant the whole farm to it, of course, but you can start trying to see f it works for you. The other important thing of that is by releasing it commercially – for utility patents, two of the hurdles to cross or ways that a utility patent would not get granted is if something’s already in the public knowledge. So here’s a couple publications. And Rachel, if people are interested, we’ll have them around and Rachel might have them in the transcript, where we published on what we did so it’s out in the public space. And the other thing with utility patents is the first to commercialize. So Edmund has a quick delivery approach for these genetics. It is really helping to keep them in the public space by getting them out in the world as commercial cultivars, which means that there can be no utility patents on these genetics because it’s public and has been commercialized. So it’s old news when it comes to patents. And if you know me, you also know that next I’m thinking about squash. But Edmund, as I said, is, uh, has surpassed me at downy mildew resistance breeding, so I’ll turn it over to him. I will note though, in that he does have a slight advantage, which was the disadvantage to the growers around his area is that he gets downy mildew a little earlier and a little bit more consistently than we do in New York. However, that’s not to take away from the man’s skills.

Edmund Frost

Thanks, Michael. All right. I’m going to share screen as well. So I’ve been growing seeds in Virginia since 2008. And I always just had an affinity for cucurbit crops, I just like the way they grow. Not sure what it is. But I noticed within the first, actually not really the first year, but the second year, I started really noticing the downy mildew problem. And just that, you know, I had the seed crops that, that were not working well, the leaves were all dying. This is a picture in 2010 of a seed crop, a cucumber seed crop that… it set, you know, it set fruit, and was starting to mature the fruit, but then the leaves all died. So you know, that wasn’t a very productive seed crop there, probably got a little bit out of it. So that’s me, there’s a picture of me with a tour, kind of thinking about what the hell happened to this crop. And so the next thing that happened was, you know, I had an interest in, in figuring out something better. I didn’t want to keep growing these crops that didn’t work. And I was learning about downy mildew. And then I went to an Organic Seed Alliance conference and went to a presentation about variety trialing. And actually, I think I met Michael at, at that conference also. So started thinking about doing variety trials to find, find seed stocks that might work better. So I started, started doing that actually 2012, 2013 – I did some small variety trials. And then I got a SARE grant in 2014 to do a bigger trial for cucumbers, winter squash and melon. I did, I did more than I should have done in that trial, but got a lot of information. In one of these pictures here, you can see that the winter squash trial, you can see this, some squash around the edge that has really died back from downy mildew. The cucumber picture’s less far along, the downy mildew hasn’t really hit yet. But I tried something like 30 cucumber varieties in that trial. And I tried, I don’t know, 20 squash varieties and 20 melon varieties. And so I had all kinds of questions about how to do this, how to lay out a trial, what to evaluate. And I was always able to call Michael and just ask, ask the questions and be able to get it done right. So that, you know, at that point, we were really starting a collaboration that was valuable to me. And what was valuable to Michael was that I’m in Virginia. And so I was able to try out a lot of his material under conditions with heavier downy mildew and give feedback. And this included the ‘DMR-264’, variety. And then a little bit later on the ‘DMR-401’ variety. And let’s see… The ‘DMR-401’, if you, if you saw Michael’s picture, it looks like it’s less resistant, but actually it’s more productive. So in some ways, you know, it’s, it’s, it’s putting his energy into the fruit. And that’s a really, really notable variety, I think has the best resistance out there. So in this trial, the, let’s, I’m gonna mostly focus on cucumbers. I was able to identify a handful of, of seed stocks that did well in the trial that… And I was looking at both disease ratings of the leafs – I would go through every week and rate the plants – but I was also looking for productivity, because you know, plants that do well in terms of the leaves looking good, but don’t produce much fruit, it’s not really what, what I’m looking for. So to some extent, you can kind of rate the productivity or you rate the downy mildew resistance by looking at the productivity. So I found a number of standouts. There was actually several Chinese cucumbers that were standouts in addition to Michael’s ‘DMR-264’. And a couple, couple other strains hat he gave me. And that trial was not only… It was not only a chance to look at the performance of Michael’s stuff, but it was a chance for me to find parents for breeding work that I started. And so we’re gonna look at some of that. This is a trial a few years later, in 2018. Another cucumber trial, you can see in the foreground, there’s some, some entries that are looking pretty crispy, and some that are looking a little bit better. And now we’re just going to look at a few, sort of, close ups. This is a picture of ‘Marketmore 76’ which is a standard slicer. It used to be, you know, listed as a downy mildew resistant variety. And this is a picture of it looking mostly dead. This is at the end of August in this 2018 trial. This is ‘DMR-264’ looking very alive. ‘DMR-401’ looking almost as alive as the ‘DMR-264’, but more productive. This is another line from Michael. This was, you know, I don’t think we continue to work with this one. This is another non-resistant cucumber called ‘Sumpter’, mostly dead here. This is a, this is a Cucumis, Cucumis anguria plant, it’s, uh, called ‘West Indian gherkin’, that I put in the trial, it’s very, very downy resistant, it’s you know, something to consider. And then this year is a picture of the variety that, that I started working on, which is, this is, this is the F3 that I entered into the 2018 trial here, and it’s doing, you know, doing pretty good in this picture. I’ve continued to work on the fruit shape and do, do more selection, which you’ll see. So that’s, that’s what some of the fruits look like now. It’s a picture of some of the fruits, going for the pickler shape. I don’t have the best picture of it, unfortunately, but… So, I just want to show you the parents. So there’s three parents to this variety. I’ll start with this one actually. I got this from, from the GRIN system. I actually got quite a, quite a number of seed stocks from the GRIN system. And I was looking at research that other people had done. I’m forgetting the name of the person that put out this study, but someone had evaluated – a professor from North Carolina had evaluated maybe hundreds of accessions from the GRIN system for downy mildew resistance so I got information from that and I took some guesses and this was one that I really liked. It did well for downy mildew resistance, productivity, and also bacterial wilt resistance, which I’ve been looking at too. You can see the Chinese cucumber fruit shape there. And it’s, this is the same 2018 trial here, it looks, it looks pretty good. But you know, it’s got, definitely got downy. The other parent is a cucumber from the Philippines that has good pickling quality, also moderate resistance. And then the third one is an American pickling cucumber called ‘Homemade Pickles’ that, you know, not resistant at all, but may get a little better than some of the other ones. And so, I actually crossed the Chinese cucumber and the cucumber from the Philippines first, and I did a little bit of selection with that. There was actually really heavy cucumber beetle pressure to select in. So I was happy to find a plant that did well in that situation. I crossed that to ‘Homemade Pickles’, and then started selecting. And here, here’s that F3 again, already have, you know, some good resistance and productivity. I have taken the approach of, you know, every year since then – every year starting in 2017, really – growing that population, looking at the individual plants, and taking notes on flags that are each… each plant gets a flag. So I take notes about the yields, and about fruit characteristics, I taste the fruits. So I look for my favorite plants. And then I wasn’t really set up to do the, the propagation of the best plants the way Michael is, but I have a longer season. So my approach has been to, you know, harvest for a week, for a couple of weeks and start identifying my favorite plants, and then self-pollinate those or sometimes cross my favorite ones to each other. I could just self-pollinate all of them, but, but I like to cut down the work a little bit. So that’s what I’ve been doing every year. This is 2018. This is the 2019 version. I actually got a grant from Organic Farming Research Foundation for a couple of years of this work. Something else to note is that it’s possible… I’m able to grow two generations of cucumbers in a year. But the first generation, I can’t really look at downy mildew. So it can work to sort of mix up the genetics or advance a population but not really to do the downy mildew selection. You can also do bacterial wilt selection in the early generation. So I did that in 2018. But after that, I started… I asked a grower in Hawaii who is actually on this on this workshop – Jay Bost – to, to do winter increases for me, because I, you know, I’d have a few fruits from my favorite plants that had underdeveloped seeds. And what he did was grow those, harvest seeds over the winter, send me back the seeds, you know, a good quantity of seeds to be able to work with the next year. This is the 2021 pickler breeding trial out of that same population. I’ve also… a slicer line came out of it as well. There’s a picture of that. And I think it’s definitely… Just one last thing -this picture, if you look on the left of this picture here, it’s, this is a Variety Trial in 2021 that includes a lot of, a lot of new lines from Cornell including a lot of picklers. So 2020 and 2021, Michael and I have been continuing to collaborate on trials and sending material back and forth to each other. And I think I’ll leave it there for a minute. Pass it back to Michael.

Michael Mazourek

Oh, yeah, I think that, in this is the kind of, as we’ve mentioned a little bit the collaboration part is, I think there’s a lot of what we do that’s probably going to be really similar. It is, kind of, going to be how a lot of public sector breeding work happens, where there’s only a few university public sector plant breeders left in many cases, for vegetables in the Northeast, there’s three of us. So you’re all set as long as you like squash and kale, and cucumbers. But so there’s some, some stability with the seed archives we have, there’s some technical insight we have. And it’s something we can share with people like Edmund, who are the other, I think, public sector plant breeders – public/private, kind of both, doing the public’s work for sure. But with, with insight that is at least as impactful and valuable, where we can share back and forth, Edmund is working with genetics are very different than mine, which is so important. Because if I was just doing mine, and then we get the next resistance breaking strain, we’re back to start. So since Edmund is working on alternatives, it’s not like, “Which one of us is like, the better one, etc?” It’s like, yeah, you need, you need it all. And hopefully, maybe three or four more people having some alternatives. So it’s, I think, it is the type of working together that I’m glad to do, to do more of for sure. And I hope there’s some other people that are working on it, too. So let’s have a shorter vignette about some squash. But squash is really just a way for me to be thinking about diversity in crops and how that is scattered across the globe. And then how do you recapture some of that diversity? I’ll be maybe talking about things in a very kind of component sort of way. It is not that I don’t love my plants. You know, it’s kind of love/hate sometimes. But it’s person… Not to say there’s not a personal relationship with them and there’s not that appreciation on that level. But we’re going to talk about the genes and the genetics, it gets rather component-ish, right? And so, in that, one of the things it’s… so how does biodiversity change? How does the, our genetic reservoir of all the natural genes in a crop – how is it scattered across the world? How can we bring it back together? So a little bit about squash. So some maybe some new new thoughts in an area maybe a couple of you have heard me talk before, but there’s many species of squash. They are grown throughout the world, in many different environments for many different uses. You know, jack-o-lanterns and acorns and delicatas in the Cucurbita pepo. All the squash with those corky, wine bottle cork-looking stems, the C. maximas – ‘Rouge vif d’etampes’, buttercups, Kabochas, the giant world record ones. And the tropical pumpkins, which also includes Butternut, that are just resistant seemingly to everything that, alas, the pepos and maximas are not. Maxima especially is so delicious, and so odds-stacked-against-it. So as we’re looking at the diversity in this Cucurbita genus in these other species, with varying levels of difficulty, they can all be crossed together. But they all share a couple issues where they… There’s this, many crops have this – Cucurbita maybe a little more than some – went through a big genetic bottleneck. And so we’ve lost a lot of diversity. You know, things like mass extinctions or something or a few plants and a founder effect. We don’t think we have a perfect idea of what that was. But there is somewhere, in the development of the genus and pre-humans, a lot of diversity was lost. In terms of genetic diversity, there’s not a ton in Cucurbita. You can self-pollinate them – there’s no inbreeding depression, which means you can’t make things worse for the plant, so self all you want. ‘Success Pm’ is a variety from Molly (Jahn), my predecessor, that’s out in the world. It’s an F22 – 22 generations of selfing it’s still… There’s, there’s usually rumors of very little heterosis, right. So that’s kind of an intriguing thing. So there are, though, ways to recover some vigor, get some interesting traits, right. So there’s an inter-specifics and so popularized in some schools of thought in Oregon, ‘Tetsakabuto’, which is a rootstock, really disease resistant for grafting. I have tasted it at a Culinary Breeding Network Showcase. It was so delicious. We can’t grow it that way in New York. We’ve tried. But it’s in inter-specific squash that allows you to take what diversity that’s left and bring it together. Similar thing, Dick Robinson made the cross in the ’80s, it was foundational to what became ‘Honeynut’. That also – butternut by buttercup – that’s what gives it, the kind of, nice starchiness. He was maybe looking for some more pro-vitamin A at the time. So to help us figure out – so how can we best look at these? Edmund can do great trials. They are beautiful; if you’re seeing the photos, we… they’re so great. Bu,t so, even Edmund probably will not be able to trial all 1300 Cucurbita accessions in our germplasm bank. And so we use the genomic approach, where we did a genotyping – not really sequencing the genomes, although we’re working on that next – but a way to fingerprint the genomes of everything that was available in the USDA’s germplasm bank. So I’m showing a map with the three species and the countries of the world they were derived from. But keep in mind, they were all derived from central South America, up into like, southern U -, southeastern US is kind of their range. So they’re collected from across the globe. But they’re all originally from one part of the globe, where all the heroic domestication first happened before all the other cultures that met them co-evolved with them. So as we look at the genetic diversity, everything that’s there and it’s separated by species. So I have just a couple plots here, some rainbows. So if you were looking at the left side, so there’s these rainbows, zigzaggy plots, these are structure plots. So for each species, there’s different colors that represent how much of the genome, basically, they have in common with each other, and what part of the genome. So there’s yellow, that’s spread across multiple groups there on the x-axis. We’ve improved these further, we’ve got some more groups. So in Cucurbita pepo, there’s now about 10 groups who’ve been able to resolve. This will be published soon. Chris Hernandez, brilliant graduate student, I think about to be my colleague in the squash space, too. I’m very lucky to have some former students as colleagues in this space. Even our humble moderator, I count in the lucky-to-be-with group [Rachel graduated from Michael’s program at Cornell in 2017]. So, right. And so what these are representing is, so you see, which are the groups that are genetically related? So what are the branches on the family tree? And now that we can see. And we can also do a plot that separates that out in two dimensions in PCA plots, where I can talk to you about some of the genetic distance things going on. But more importantly, what you can see is there’s different colored, there’s blobs of different colored dots coming together. That represents all the different geographies where the plants were from. So what we’re seeing is, there are… as we think about market class, or you think about what country something is commonly grown in, that’s a really good predictor of the genetics of it. And so, on one hand, if you’re thinking about breeding, you’re trying to think about how to get genetic diversity back into a very non-genetically-diverse crop. At least I can tell you for Cucurbita, for squash, crossing between countries and market classes, (something people rarely do in the commercial sector, where you want to make, quickly improve your latest hybrid to get next in the market), where you’re doing more open wide crosses, these are the crosses you can do between species or just between market classes, you’ll get some pretty good genetic variation in the population, you’ll have. Some of our greatest creations have come from that approach, before we really knew we were… we noticed we were doing it but we didn’t know there was any scientific backing for it. Now we’re starting to see it in what we’re bringing together from across the globe. It’s also an interesting thing to think about the… what it means to conserve genetic diversity, what it means to work with different crops from around the world, how these ex situ conservation protect diversity… And there’s some, something there we’re digging into this more, but if you think the, where a crop was domesticated, it had all the genes, right? And then as that, it got moved across the globe, there’s been different subsets of it. But both are continuing to change. So as people grow, cultivate, interact with the plant in all the anthropogenic ways, you’re bottlenecking the genetic diversity as you’re trying to make it better, right? And so in doing that, you’re losing some of the variation that was once there, but you still have it, if you find the seed that ventured across the world, to other areas where they had different goals, different conceptions of what that plant should be to their culture. And so they kept different subsets of the genetic diversity. And so it’s a space I’m really interested in lately, and both in terms of kind of breeding progress and kind of what it means for beyond the center of diversity being the archive of all of the variation of a crop. So looking how the globe has become the archive of a lot of the variation of a crop. I have a lot more questions than answers there. But that is a space that we’re really excited to think about. If people want to geek out in the Q&A, we can also talk about the allo-tetraploid origins of the Cucurbita species- genus, etc. But I like to hand it back over to Edmund before that. Can’t hear you Edmund.

Edmund Frost

Okay, thanks. Yeah. Yeah, that was really interesting. I didn’t fully understand the graphs but I’m gonna, gonna look at them some more later. So, yeah, that reminded me to talk about, you know, that I want to talk about Cucurbita moschata. So that is the, that’s the squash species that does the best in our region, and in a lot of the, you know, a lot of warmer parts of the world and I’ve been doing a lot of work with it. As much as cucumbers, really. You can see in the picture that I have up now, I mentioned the cucumber variety trial on the left, there’s a melon breeding trial in the middle and then on the right there’s a squash breeding trial. You can see some orange flags that, you know, that have names on them. And then…it’s not… okay. This is a, this is a breeding trial from 2020. Each flag is a different plant. And you know, notice, like, the cucumbers how I keep them trained separately. Learned that from Michael, because otherwise it just gets too confusing. Something that struck me about moschatas lately… So, so about my, my moschata breeding work – the first thing that I did was I crossed ‘Waltham’ butternut with a ‘Seminole’ pumpkin. And that was 10 years ago. And then started selecting that for downy mildew resistance. I got downy mildew resistance in pretty quickly, but then was selecting for fruit shape and, you know, eating quality and yields and keeping quality. And I think it’s a good variety in a lot of ways. But it’s… I don’t know, it’s an enigma in that Cucurbita moschata, and this selection project continues to surprise me in terms of, I think there’s been times when I’ve thought I’ve been making a great selection and maybe, maybe it wasn’t the best direction to go. And the, I think the, the biggest drawback of of the variety that I bred – it’s called ‘South Anna’, named after the river that, that is near here – it’s uh, it’s kind of indeterminate. So you know, you want to go through and harvest it twice, which is not necessarily the most desirable trait for butternuts, but you know, that is what I do. And so that, that was, you know, was working for me. It’s got great eating quality and downy mildew resistance. And I’m still selecting for that stuff. But then I took that and I started crossing it to other stuff. And actually, Jay, Jay Bost again, did some of these crosses for me. There was, there’s a squash from Guatemala that, that we crossed it to that ended up having really good, really, really good keeping quality. There’s a Chinese pumpkin that I crossed it to. That one, the the straight cross of those two was a really poor yielder. It didn’t work out very well, but then I backcrossed it to, to my butternut project and then a did great. And it’s really interesting because that one actually has excellent keeping quality. The Chinese pumpkin doesn’t have good keeping quality. And my butternut has sort of moderate keeping quality, but the cross of those two ended up having excellent keeping quality. It just, you know, there’s another story where the F1 generation of, of a cross had good, it had sort of moderate eating quality. And then, for some reason, most of the F2 plants had just like, incredible eating quality. And I didn’t know why. Just kind of keeps throwing stuff that I don’t expect, which is exciting. And I’m excited about many of these new crosses that I’ve been doing, especially for keeping quality, for determinacy, and for different flavors. This is a breeding trial of something that has 25% of Johnny’s butternut crossed into it, and then selected over a number of years crossed with with my variety, ‘South Anna’. Has really good eating quality, smaller size, it’s productive, but not a great keeper. I put it out there this year as ‘Butternut 200’. Because I wasn’t, I wasn’t sure it was good enough for a real name quite yet. I just wanted to look at it a little more, but I wanted to share it anyway, get started sharing it. This is the ‘South Anna’ variety. You can see it’s kind of variable on size and shape. And that’s because I wasn’t really focusing so much on that, that. I was focusing on, you know… I wanted fruits that were some kind of butternut shape. But then I was more focusing on disease resistance and flavor, yield. And, yeah, this is a picture of a Halloween pumpkin project I’m working on. This has, it’s a pumpkin from New England crossed into, crossed with a Mexican variety. I did a, I did sort of a screen of a number of Cucurbita pepos from… I tried to find ones that were probably from more humid coastal areas of, of Mexico and Central America. And one of them called ‘Tutume’, did, you know did really well in the late season and I crossed it to this pumpkin from New England. And so I’m working on that. And see, yeah, I think I’ll leave it there. I was going to talk a little bit about bacteria wilt resistance selection. You know, there are other things besides downy mildew that I look at and care about. And, and I think, you know, that I consciously care about but then there’s, there’s ones that, that just by selecting them in organic conditions are probably you know, getting stuff that’s pretty overall resilient for our conditions. Like a little bit of squash, you know, some squash bug resistance and stuff like that. This year, this last picture is a, is a bacterial wilt cucumber trial. So I would love to see more work done on that as well. I did a couple of trials. And it’s kind of elusive, but I think that, I think that my variety has pretty good, you know, it holds up to it in the field. It can still get it but yeah.

Michael Mazourek

I don’t think we can hear you, Rachel.

Rachel Hultengren

Is that the end of the presentation that you… okay. I didn’t want to jump in and declare, like, the Q&A if you still have other things you wanted to share.

Michael Mazourek

Yes, uh, yes – please lead us, Rachel.

Rachel Hultengren

Wonderful. Thank you both for the presentation. So we’ll have about half an hour for a Q&A. And either, if you’d like to drop a question in the chat, I can ask it for you or if you’d like to raise your hand and let me know that you’d like to ask a question in person, we can do it that way, too. So Julia asks, in the chat, “Michael, can you define market class for us?” The term you used?

Michael Mazourek

Yeah. So there’s probably some better horticulturalist definitions out there. But you can think of it as the group, the category something would be sold in, like as a commodity. So like, you’ll see butternut squash, acorn squash, delicata, you might have flint corn, dent corn, sweet corn, many others. So it’s whatever… there’s different categories that you would, you might identify something being in, so whatever category you would see for a plant. Why that tends to matter is, like, say you have zucchinis. Once you are into zucchinis, and improving zucchinis, you’re going to tend to be crossing the the plants that are most zucchini, working within zucchinis crossing zucchinis to zucchinis. When you have… my colleague, Jim Myers, talks about stringless snap peas or snap peas. There’s a lot of genes that make a snap pea succulent and edible, that, like, garden pea, shelling pea, dried pea certainly lacks. And so, if you’re wanting to make progress, you’re typically thinking about crossing a snap pea with another snap pea. If you’re feeling adventurous, you cross it to a snow pea. So you’re working in a very narrow space. And that kind of takes you on a downward genetic spiral, where everything gets more and more similar. Potatoes are a complete exception to a lot of things there. But yeah, so it’s just kind of that, you know, maybe you think about what you would label it as to buy it or sell it, how you’d group it – that’s a marketing class. And that’s why they’re, kind of, get so genetically coalesced. And then if you’re looking for variation it’s between things you would assign to different groups. And, yeah, have some more, more to wander around thoughts there. But maybe there’s a question for Edmund.

Rachel Hultengren

Yeah. Edmund, Jay asks about the training techniques that you mentioned with the cucumber photo that you showed, and what sort of spacing you use between the plants.

Edmund Frost

Yeah, so cucumbers, if I’m training, like, if I’m looking at individual plants, I’ll plant them about two and a half feet apart. And at two and a half feet in the row with the rows about six feet apart. So that’s, you know, it’s a good bit wider spacing than you would normally use. And then for the squashes, it’ll be more like, six or seven or eight feet apart in the row, and then 10 feet between rows. Sometimes I wonder if I’ve been… So there can be some downsides to training, especially with squash. I’ve noticed that, like, more incidents of sunburn with, with squash that’s been trained, so you might reject plants that, you know, that have sunburned fruit, but that wouldn’t have happened if you didn’t train it. I think you can, you can address that by training more often. So you want to do it twice a week when it’s busy. And you know, if you let it go longer, you’re gonna, you might end up with problems. And sometimes I wonder about, you know, I have done grow-outs where I trace the squash, where I let them intertwine and then trace the squash back. And I think there’s some strength to that. I actually want to do more of that. I’m not gonna get so much of a downy mildew read on the leaves, but I’ll get to look at the fruit and the productivity and taste it and it’s more work chasing the fruit but it’s less work training.

Michael Mazourek

And we… one of the big things when we go to the plant breeding spacing versus production spacing… In production spacing, the canopy so beautifully blots out all the weed pressure. Once you get to these wide spacings you’re just, if you want to tell the vines apart, you have a lot of daylight for weeds to come through. We’ve done things like rolling, rolling round bales of straw through the fields to be a nice mat when we’re trying to keep it organic. There’s some plants where we can’t, we’re on the conventional side of fields where they do herbicides, there, but the… We’re always trying to do it better. And so one of the things we’re starting to do is, you can get other squash you can tell apart, other cucurbits, like the West Indian gherkin, I think Edmund had. So we’re starting to use those as the separators between plants or putting rows of a bush squash you want to grow or when you’re going to do on farm work, there’s ways to set up different borders, so you’re still keeping the neighbor competition pressure to see how stuff does, when it’s not just the only squash you can see. But still make it so you have a prayer of finding them, telling them apart. Our days, where we find a fruit we like, and we tug on it to look around within like a 20 foot radius to see where the Earth moves. That’s not our most favorite harvest days.

Rachel Hultengren

Julia, I see your hand, but Craig has a question that I think goes with what we’re talking about right now. So maybe we can hold for just a second on your question. Craig asks, “Is pruning part of the training method that you use, Edmund or Michael?”

Edmund Frost

I haven’t done that. But I think, I definitely think you could. I just haven’t done it.

Michael Mazourek

It’s not something we do intentionally. But sometimes the, the tractors or stuff has to get through. One of the things that we know as we are doing it, that I know we’re probably missing is – a lot of these crops, they, the cucurbits, they will put down these secondary roots. So they love making roots. And whenever the nodes get kind of, a little bit buried, they’ll be trying to make some roots out, and they’re almost always trying to make some roots, with the little white dots emerging. So, you know, as, so for weed control sometimes, we’re mix- moving and shifting the vines. And so I think there’s things, I know there’s things I’m missing when I’m doing that. You know, one I hear about – so we don’t have squash vine borer pressure yet. I’m sure it’s coming. Edmund has a lot trickier growing environment than we do. We have like a lot more, a lot more and a lot colder winter to be a nice, beautiful reset and everything. Makes it easy. So, but like, when you have vine borers coming in, and so they like, girdles the base of the plant, like really bothers the base. Some varieties can keep growing through that and I think it’s probably related to how much other roots they’re, kind of, putting down to help feed some water in, into the system.

Rachel Hultengren

Julia?

Julia

Yeah, do you guys ever intentionally add stress to increase the selection pressure, like drought or introducing other diseases?

Edmund Frost

The main stress that I add is just planting late when there’s more downy mildew. So like my cucumbers selections, I’ll plant them, like, in July.

Michael Mazourek

Yeah, and we, we do some, you know, add – inoculate with some some pathogens in the greenhouse sometimes. We try not to add any outside. So, like, when we’re working with a fungus or a virus in the greenhouse, we’re working with ones that are already around. But we are trying to, I’m trying to wrap up in the early spring when it’s still freezing weather and it, it can’t, if it is blows out the greenhouse vents, it won’t establish or, kind of, get in the area a little earlier. For cucumber beetles, we’re usually trying to moderate this stress. We’re in a space where we want most of the plants to live and look good. And then to be able to whittle it down further in some cases, we’d like most of the plants to hurry up and die and we can just take the survive- the fittest. With cucumber beetles and cucumbers, with some of the types that can be bitter, it’ll really show up if the cucumber beetles get after them. We are starting to do some drought work in some of our high tunnels. So we’re just starting to do that because where I am, there’s a lot of growers still don’t have irrigation for much of this season because they just count on the rain. And so when the rain doesn’t come they’re running around trying to drill wells or, you know, and, and then the next couple years won’t be an issue, so it’s like this every-few-year disaster. So yeah, the, the Gothic NRCS-type high tunnels are fantastic for drought screens. The caterpillar tunnels, not so much. But NRCS, those run really, really desert-like.

Rachel Hultengren

Jack?

Jack Kloppenburg

Good evening friends. Can you tell me how open source fits in to everything that you’re doing? Are you planning on pledging any of the varieties you’re developing?

Edmund Frost

I could go. So my squash, my butternut squash lines are pledged. I pledged, pledged them several years ago, and then I keep making crosses off it. So that’s the ‘South Anna’ and the ‘Butternut 200’. And there’s, there’s more that are coming. And I’m definitely excited to be part of it. You know, part of a movement that is, you know, working on countering corporate control of seeds. And I think that this is one, one tactic. And I’m definitely interested in other… you know, I don’t think it, I don’t think it answers everything, but it’s, it’s one, one way to address it. And, and, you know, keep, keep stuff from getting, getting privatized by corporations, you know, stuff that I put out there. So I’m excited about that. I’m actually, I’m, I’m trying to decide whether to pledge my cucumbers. And I have some… I think my, my biggest thought on it is – I almost wish the pledge was shorter, that it was something that you could just, that you could say, orally. I have this hesitation around asking a pledge to accompany the seeds, you know, forever, indefinitely. In terms of just, you know, I want… I, I believe that these seeds will outlast our legal system and our language, you know, and they’re just, you know, the seeds and their descendants. And, and so, I have this hesitation around saying, like, “This written pledge is going to always go with the descendants of these seeds.” So that’s something I’m trying to work through. But I think that, you know, as a tactic, and that… I really appreciate the OSSI pledge, and I’m glad to be part of it. And I’m just, I’m just thinking about, about, about this question.

Michael Mazourek

Yeah, and I, I joined the, the OSSI board, as I wanted to explore with what it meant more because I… Around the time that utility patents started happening to plants, Cornell started using Material Transfer Agreements. It’s actually the… out of vegetable breeding is where the genesis of it was. My predecessor started doing it. And in part, one of the things that was going on is using contract law to be able to prevent ownership claims or privatization or… It was using some of the paperwork in a defensive way. It means that all this paperwork has to follow the seed, so every time it changes hands, we… The people are directed back to Cornell, and there’s reasons why- when that makes a lot of sense with stock seed, with a variety being the same out in the world, et cetera, for us to be able to make sure they understand the expectations and non- patenting, etc. Not every reader Cornell approaches it the same way, but this is how we do. That, the system seemed to be serving us really well, up until I started working with freelance plant breeders, participatory plant breeders that were want- that were trading seed with each other. When you send seed to seed companies, they’re seldom… The major seed companies are seldom really just getting together at seed swaps and sending seed around. So that hadn’t been a concern, but as I’m working with the different groups, people with the vari- uh, Bauta Family Initiative and Canada… seed system… There are a lot of groups in Ontario, especially. (Hi, all of you.) And so, as they have, like, the group project approach to plant breeding and community plant breeding, our, kind of, tracing every seed and accounting where it is, monitoring it, essentially, wasn’t really the best fit. There’s, there’s a lot of parallels and similarities, I think an, an opportunity to harmonize what I was doing at the university with OSSI, if we, you know, learned more and, kind of, explained to the university what was going on and figure out so… I also have questions about, like, what does it mean to “restrict”? So when we say you won’t restrict, exactly what does that mean? So how can we, if we can figure out what everybody’s intentions are, and write that down, then that, I think helps the the OSSI seed be OSSI seed, but also helps us understand how other people can really understand it more and maybe participate even if they hadn’t been in an institution that would have considered it before.

Rachel Hultengren

Carol, it looks like you have your hand up. I’m afraid I, Carol, I can’t unmute you. If you could press star six, that’ll unmute you.

Carol Deppe

Okay, I have some basic questions about the biology of the powdery mildew. You’re, you apparently have problems with it.

Edmund Frost

It’s downy mildew, Carol.

Carol Deppe

Or excuse me, downy mildew,

Michael Mazourek

But I can take powdery mildew, too, if you want.

Carol Deppe

Let’s stick with downy mildew. The downy mildew – is it the same lines that are on the squashes are on the cucumbers, for example? And the same lines that are on different squash species? Or is it different lines?

Michael Mazourek

So there’s two major clades, two genetic groups of cucurbit downy mildew, the pathologists tells me. We’ve seen it happen where one effects, is the most symptomatic on cucumber and the other is the most symptomatic squash or is more symptomatic on squash than the other. So there’s, kind of, the cucumber, and everything else, and the squash –Cucurbita – and everything else. So they cross over, but they’re distinct. And so I normally get the cucumber strain. We don’t usually, it varies whether the squash strain will be in our area. But when it is the squash get whacked. I think, and Edmund, I think, sees his squash more reliably affected by downy mildew.

Edmund Frost

Definitely.

Michael Mazourek

Yeah. So it varies a little bit based on, on season, which one’s gonna blow in. It also… we… there’s very little facts about where it overwinters. You know, probably in the Florida Keys where it doesn’t frost and there’s always some wild cucurbits is a pretty good bet. How it then has the, shows up also in Michigan and the Great Lakes also really early on – it’s unknown how it gets there. There’s a lot of finger pointing, how it gets there. But, so, there’s some dynamics of what’s going on that really… Yeah, it’d be so helpful to be able to know what’s going on so that we could have more, some more targeted efforts.

Carol Deppe

We don’t, as far as I know, we don’t have downy mildew on cucumbers or squash here in the Maritime Northwest. Is that right?

Michael Mazourek

Yeah.

Carol Deppe

And are you expecting that we’re gonna have it?

Edmund Frost

I get… there’s, we have customers from California, parts of California that, that get it that order from us.

Michael Mazourek

That’s starting to pop up. There’s a website, it’s a long website. But it’s a, it’s a, it maps the movement of cucurbit downy mildew across the, forecast so you can hear when it’s nearby. When it’s, it gets to jump to your county. So you can see where it is on, on the, in the US. Globally, there’s, it’s also an issue, but not so much the mapping tracking effort. But it’s the East Coast, the Gulf Coast, and then some, like Southern, like halfway up California is the highest I’ve seen it. And then the Great Lakes. About it’s, you know… I think the, the Pacific Northwest, like, the when, when hops downy mildew showed up in the Northeast, you know, that, we lost that industry. And that’s when it moved to the Pacific Northwest as well. You need that alternating really wet and dry. So that’s what it needs to complete its life cycle. So I think Corvallis is probably safe for the foreseeable future.

Carol Deppe

Thank you.

Michael Mazourek

And to follow up on a notion from Edmund a while ago about my, my crazy graphs – so, I think, so, what like, so if you’re a freelance… If you’re interested in crossing squash, it’s like, so what do you do with that? So what we’re going to be having, hopefully really soon, is, kind of, the information about which different genetic groups, you know, like, what’s the family tree of squash? And what squash are in different groups? And if you have one that’s not there, that you would like us to help figure out which group is, it’s in, we’ll be able to be much faster at that. So you know, there’s some that – ayote, for example – that wasn’t in our screen, to our knowledge. So if you’re interested in where that was placed, kind of, there’s a lot going on with that, in a lot of ways, but to which group, but by, by us being able to usually approximate things of the geography and which commodity group you’d put it in. But if you’d like some more insight, we can help you with some of these lists know exactly what’s what. And so if you wanted to either have a cross, where you’d have the best fertility and the less, least issues down the road, this could help you. But if you wanted to really jazz stuff up and look for some hybrid vigor, we, our crosses between continents, especially, and where you have very different culinary uses etc. for the squash – that’s where we see these some of these fantastic things. Like Edmund, that he was talking about, how you take to poor-storing things and cross them together, and then suddenly, like, Eureka. We see that too, and it always turns out it’s between these groups. So we’ll have some lists that can help people navigate the family tree a little bit if they want. So I think that’s kind of the, the take-home from that for a lot of folks. It also reminds me of, I had a… Oop – Jay, I think, has a relevant thing before I move on from to my next ramble.

Jay

Yeah, I was just curious, like, you know, using that information that you’re talking about, and in that case of when you’re trying to do these, you know, relatively wide crosses, do you feel, or do you tend to want to, like, make that cross and then start selfing? Or do you feel like you can end up getting, like, more interesting recombination between these things by, like, sib-ing for a few generations? Or does it really matter?

Michael Mazourek

Yeah, so it depends how hurried you are, and how uniform you want it to be. So rule of thumb, in any recombinations happening between the squash, you know, any plant, you get, like two or three crossovers per chromosome. So you’re really cutting the deck, you’re not shuffling the deck. So the more times you’ve cut the deck, the more times that it mixes it up. Squash has these 20 little dinky chromosomes, so I think they might behave a little differently. But in general, you don’t get many crossovers in squash, if anything. So, and I think, so, if you want to really mix things up, sib-ing beyond the F1, like, selfing the F1 and sib-ing the F1 is usually pretty similar. Now, if you’re working with a land race, like, you know, where you have variation between plants, like, by all means start sib-ing, and then you’ll be getting more variation that way. But it’s, like, the generation after that, you know, keep sib-ing to really stir the pot. And there’s different philosophies about if you want to be stirring for a while, sib-ing for a few generations with patience that I lack, and then look to see everything that’s there. There’s, there’s reasons to do that – you retain more things you didn’t see, but then, my goodness, you have a huge tangle to untangle. Someone like me would like to look at the F2, find my best plants, self those, and then at the F3, start combining them together. I’m… I like to reduce the complexity of the puzzle. At the same time, I’m, I’m prematurely jettisoning a lot of stuff that would be really useful down the road. So there it becomes ,kind of like, your scale and philosophy. But yeah, sib-ing if you, if you want to really mix things up and see what all the possible combinations are, for sure. A, an observation I haven’t really followed up on a lot, but it was the thought of Henry Munger, two generations before me is that – if you, kind of, wait too long to try to get recombination, you, you start to get regions that are homozygous, and you tend to recombination happen in regions that are the same. So after you self something, and then you want to cross it or sib again, and try to get more variation, the thought then was re- the recombination would happen in the regions that zippered up the best – the regions that were the most similar. So you’d be kind of just spinning your wheels if you waited too long. That would be really cool to peep on the genomes and see if that, and see how much of that really is working. But you know, that was, that was his insight and darned if he wasn’t an insightful person.

Jay

Cool. Thanks.

Edmund Frost

Michael, do you mean, do you mean, like, if you waited too long to start sib-ing, like a few selfed too much, you, you would run into problems?

Michael Mazourek

Yeah. And Henry, Henry was the, the… One of his great contributions was he was the champion of backcrossing. So for him, he would be interested in recovering type a lot. And so he, he had a technique that gets a lot of eye rolls around, but I still have used it from time to time. And I’ve told myself, it’s made all the difference. We could probably look at something and see, but it made sense to me. So he had a technique he called the “half backcross”. And so rather than crossing back to the plant he wanted it to be like, you know, if you’re working with something that’s really bitter and spiny and etc, you want to purge a lot of that. And so when you’re doing backcrosses, he was feeling that he was having some of these issues of recovering type. And so he would cross things back to the F1 instead of to the favorite parent. And there’s some cool things of thinking about how things are still very dynamic. You’re keeping, you’re still keeping some progress. And so keeping a lot of things dynamic, so encouraging crossing-overs to being kind of random versus patchy and unproductive. And also trying to still… It has an element of recurrent selection still to it, even though you’re trying to recover type. So the half backcross, there’s a couple of essays he wrote that I think it appears in. Otherwise it does not appear in any genetics text. And that was a decision of the authors I’m sure. However, if you’re looking from a generational insight, there are some gems. One quick little ramble that reminds me of – so in cucumber, there’s this… Bill Holdsworth, one of the students behind a lot of things, but even the downy mildew cucumbers, did a lot of work in the recurrent selection that I wouldn’t have done but Bill convinced me was the way to go. And he was right too, for stacking lots of little genes is… Well, one thing from Bill’s defense seminar that stuck with me, he was talking about how it was so much work to try to take the downy mildew resistance from these wild sources in India and bring them into, like, a good, a good cucumber, like the target cucumber. And thinking about, that thought, that he shared at that moment is still, it sparks a lot of my thinking. So in one, I think, spent a lot that type of thinking about like, what makes something good? And what makes it so you’d want to try to recover something. So why is recovering types of important? And, you know, the resistant types tend to be the ‘Suyo Long’ types. Edmund showed one of those. There’s also some Poona Kheera types. So Poona Kheera – so it’d be… ‘Kheera’ is ‘cucumber’, ‘Pune’ is a big place in India. So there must be a lot of people that like that cucumber for it to be the cucumber of Pune. So some thoughts about – so what really is marketing class? How was that holding us back? I like to wax poetic around that. I won’t give you the long version here. But it’s shaped a lot of my thoughts. And the other is, that was kind of our first insights, of bringing together really different genetics. Edmund is bringing together some really different genetics – that ‘Homemade Pickles’ – a lot of pickling types had some intensive breeding for downy mildew resistance. They use a lot of Henry Munger’s ‘Marketmore’ points at work. So I think that explains why there’s some cool genetics left over in there. And then like, like I was doing with the ‘Marketmore 97’ is combining it with some very different genetics from another part of the world. And so it’s the additive nature of bringing together these very distant groups. Things that you wouldn’t consider the same cucumber gets us… That, that is the key to my downy mildew resistance breeding. I don’t know to what extent Edmund also finds that’s the case. But that seems to be a recurring theme, now, in a lot of what we do. And we’re trying to see, like, how much of that, how much we can reproduce that, like, in some of the other crops we work with.

Edmund Frost

Yeah, I’m, I’m definitely interested in, in casting a broad net to find resistance sources and, and like my, my cucumbers have a parent from China, a parent from the Philippines, that, I think, yeah… I had a really broad diversity of shapes of fruit coming from it and colors even. And I’ve actually had this new, a cross that I’m excited to start working with. I kind of re-, refound it. But it’s a Poona Kheera type cross that did well in our trial crossed to the same Chinese cucumber parent that I have in the other population. And I’m excited to just see what happens if I just, just crossed those and don’t use an American cucumber with it at all. Because it kind of seems to me like somewhere in the middle between them is kind of similar to an American cucumber. So I want to, I want to check that out. And I guess the other thing I wanted to say, in terms of like, the diversity, like, crossing really diverse kinds of squash, like I have, sometimes I’ve done it and gotten bad results, you know, so you just, just try different things. And some of them are going to be great.

Michael Mazourek

Between the, the Halloween pumpkin group and like acorn squash – so those crosses, I think there’s a lot of cool things to be done. You end up, after a couple generations, sometimes, with a surprising amount of sterility issues. So I noticed when Rachel was still with us, there were some people out in the field doing some pollinations and they were having to use toothpicks to try to scrape some pollen out of the flowers. And it, it wasn’t pretty. And so, so those, those were always doing well. Rachel’s acorn by delicata, crosses, etc, where it was within a group, and there’s not like, there’s, that wasn’t as much genetic variation, but there was a lot more forward progress of the things that worked and stayed working. And so…

Rachel Hultengren

Well, if we don’t have any more questions, I’d like to, to take the time to thank everyone for joining us, for sharing your time. And thank you to Edmund and to Michael for the presentation. The recording of this webinar will be available on the OSSI YouTube channel in a few weeks, along with a link to the transcript. And the April webinar on the Dwarf Tomato Project is up there now, for anybody who wasn’t able to join that. We’d love to hear from you what you thought of the webinar. And if you’d like to share feedback with us, you can email osseedinitiative@gmail.com. The next webinar in the series will take place on June 8 at 7pm Eastern time. Dr. Deppe will present on “Breeding for climate change, regional adaptation and wild weather”. So thanks again, everyone for joining and I hope you have a great evening.

Edmund Frost

Thank you, Rachel. Thank you, Michael.

Michael Mazourek

Thanks, everybody, good to talk, Edmund.