Episode one of the third season of Free the Seed! the Open Source Seed Initiative podcast

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 46:00 — 52.1MB) | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

This podcast is for anyone interested in the plants we eat – farmers, gardeners and food curious folks who want to dig deeper into where their food comes from. It’s about how new crop varieties make it into your seed catalogues and onto your tables. In each episode, we hear the story of a variety that has been pledged as open-source from the plant breeder that developed it.

In this episode, host Rachel Hultengren talks with Edmund Frost of Twin Oaks Seed Farm and Common Wealth Seed Growers about ‘South Anna Butternut’, a downy-mildew resistant winter squash that he developed.

Edmund Frost

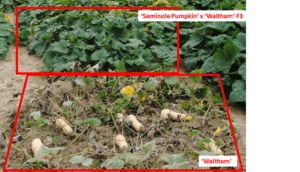

2014 Variety Trial, (‘Seminole Pumpkin’ x ‘Waltham’)F3 on top, ‘Waltham’ on bottom

Taste test from 2017 Virginia Association for Biological Farming conference

Episode links

– Learn more about Common Wealth Seed Growers’ research at http://commonwealthseeds.com/research/

– Organic Seed Alliance’s “Grower’s Guide to Conducting On-Farm Variety Trials”: https://seedalliance.org/publications/growers-guide-conducting-farm-variety-trials/

– Information on the patent on using the PI197088 cucumber for downy-mildew resistance breeding: https://patents.google.com/patent/US9675016

– Carol Deppe’s Books: https://www.amazon.com/Carol-Deppe/e/B001K80VOQ%3F

Show Survey

Let us know what you think of the show!

Free the Seed! Listener Survey: http://bit.ly/FreetheSeedsurvey

[gdlr_button href=”https://osseeds.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/S3E1_SouthAnna_Transcript.pdf” target=”_self” size=”medium” background=”#5dc269″ color=”#ffffff”]Download the Transcript[/gdlr_button]

Free the Seed! Transcript for S3E1: ‘South Anna Butternut’

Rachel Hultengren: Welcome to Episode 1 of Season 3 of Free the Seed!, the Open Source Seed Initiative podcast that tells the stories of new crop varieties and the plant breeders that develop them.

I’m your host, Rachel Hultengren.

This podcast is for anyone interested in the plants we eat – farmers, gardeners and food curious folks – who want to dig deeper into where their food comes from. It’s about how new crop varieties make it into your seed catalogues and onto your tables.

In each episode, we hear the story of a variety that has been pledged as open-source from the plant breeder that developed it.

Rachel Hultengren: Our guest today is Edmund Frost. Edmund is an organic farmer and seed activist based in Louisa, Virginia. He focuses on several aspects of Southeast regional seed work, including seed production, plant breeding, variety trials research, and variety preservation. Edmund runs a small seed company called Common Wealth Seed Growers, and co-manages seed production at Twin Oaks Seed Farm.

We’ll be talking today about ‘South Anna Butternut’ – a butternut squash that Edmund has been working on for the past 9 years.

Hi Edmund – welcome to Free the Seed!

Edmund Frost: Hi Rachel, it’s good to be here.

Rachel Hultengren: So I’d like to start by talking about the impetus for this project. The primary trait of interest with ‘South Anna’ is its resistance to downy mildew, a fungus-like disease that affects plants in the squash family. So I’m curious – what was the process of deciding that this was a project you wanted to take on? did you talk with other farmers or gardeners that told you that this was something they needed, or was it personal experience that mainly drove that decision?

Edmund Frost: So I started the project in 2011, quite a while ago now, and it was based on experiences of having Cucurbit crops that died from downy mildew. We had cucumbers, winter squash, melons and other crops especially in 2010 and 2009 that did really badly from downy mildew, so it was really on my radar from that. And I guess in 2010 we had a ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ seed crop that did quite well despite the downy mildew pressure. So I noticed that, and I was excited about it, and the next year I thought, ‘Well, I’m growing some butternut, just some ‘Waltham Butternut’ for produce, and why don’t I just plant some ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ plants next to it?’ So that’s really how I got started, was I just grew the two varieties together and let them cross. And I didn’t know a whole lot about plant breeding at that point, but that’s how it started.

Rachel Hultengren: So I’d like to ask you how you decided on ‘Waltham’ and to describe the ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ a little bit more in just a minute, but maybe you can tell us a bit about downy mildew. So what does it look like if a field of cucumbers or squash is infected with that disease?

Edmund Frost: So downy mildew, unlike powdery mildew which shows up as a white powder that’s very visible on the leaves before the plant starts to die from it, downy mildew can just look like the leaves just shriveling up and dying. You don’t necessarily see the mildew when you look at the leaf. If you look at the underside of the leaf, you can see a little bit of grey spores, but it’s a lot less visible than powdery mildew. So what you see is just your foliage start to die, and it can spread very quickly and it can easily just wipe out all of the foliage in a susceptible variety when you have downy mildew pressure that’s significant.

Rachel Hultengren: And when all of the leaves die, that can basically wipe out the crop.

Edmund Frost: Right, and it doesn’t directly affect the fruits, but when the leaves all die that stops the plant from being able to produce sugars that go into the fruit, so you end up with drastically lowered production and lower quality in fruit.

Rachel Hultengren: When you say that it doesn’t affect the fruit directly, you mean it doesn’t cause the fruit itself to rot?

Edmund Frost: Right. Yeah, it affects the fruit often dramatically in terms of productivity and in terms of sweetness, but it doesn’t cause the fruit to rot.

Rachel Hultengren: How does the disease spread?

Edmund Frost: So it has a really interesting life cycle, and it’s actually similar to Late Blight in tomatoes. It can’t survive freezing temperatures, so basically it overwinters in parts of the country – like south Florida or south Texas or in Mexico or Cuba – it overwinters in places that it doesn’t freeze. And then every year, the downy mildew spores blow north on the wind and gradually work their way up the east coast, often all the way up to Canada. There’s also some speculation that there might be downy mildew that overwinters in greenhouses, if there are greenhouses that don’t experience freezing temperatures, so those might also be a source of infection. And once the downy mildew arrives, in whatever way it arrives, the amount of spores keep building, and the more spores you’re producing in your crop, the more it’s gonna sort of exponentially keep affecting that crop and the crops nearby.

Rachel Hultengren: So it’s not something where if you manage your soil really well and you manage the disease by rogue out individuals that have it and getting those off your farm… because it blows in on the wind every year, there’s no way for one given farm to be immune to it, other than growing resistant varieties.

Edmund Frost: Yeah, that’s my assessment. I think looking for resistant varieties is central. Most varieties that we commonly grow as market farmers are not resistant. I’ve had to look further afield to find resistant sources, and that’s for ‘South Anna’ and other winter squashes, but also for the downy mildew resistant cucumbers I’ve worked on.

Rachel Hultengren: Tell me more about the ‘Seminole Pumpkin’. What’s the story behind that? Where did it come from, and what does it look like?

Edmund Frost: So ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ comes from Florida and it can actually grow feral in Florida. And I don’t know the exact origins of it, but native peoples have been probably growing that variety or something similar for a really long time. The strain of ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ that I’ve been growing was, I believe, introduced by Southern Seed Exchange. It’s the color of a butternut, a little deeper tan, and they’re usually 2-3 lbs, and either round or tear-drop shaped. And it’s the same species as butternut, which is Cucurbita moschata.

Rachel Hultengren: That reminds me – I wanted to point out that word ‘pumpkin’ often makes people think of jack-o-lanterns, but as you’ve said, the ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ is in the same species as butternuts, and that’s actually a different species from jack-o-lanterns.

Edmund Frost: ‘Pumpkin’ is not really a precise botanical term. It’s a folk name that people use for varieties in any of the Cucurbita species.

Rachel Hultengren: So you started this project by seeing that ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ had really good downy mildew resistance. Was it the case that there just wasn’t any downy mildew resistance in a more traditional butternut-shaped squash?

Edmund Frost: So when I started the project, I wasn’t really working with a lot of different kinds of butternut. I had tried out three or four kinds at that time. If I was to start it again, I might have used a different butternut in the cross with ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’.

Rachel Hultengren: Why’s that?

Edmund Frost: There are varieties that hold up a little bit better to downy mildew than ‘Waltham’. None of them are resistant. None of them hold up well. But ‘Waltham’ is maybe one of the least resilient to downy mildew. But it was what I knew about. And I knew that it had good eating quality, it’s productive, it’s the shape that people want, so it’s what I used. And I think it’s, you know, ultimately has worked just as well as a different variety would have worked, ‘cause I’ve been able to get the full resistance of ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ and probably even better than that into the ‘South Anna’.

Rachel Hultengren: You’ve said that the qualities of ‘Waltham’ that you were looking for, or that you found attractive, were its eating quality and the shape that people recognize. What goes into good eating quality in a squash?

Edmund Frost: For most dessert winter squashes – something like a spaghetti squash would be a different category – but most winter squashes what people are looking for is sweetness and flavor, which is a little bit hard to measure. And then also dry matter has a lot to do with good eating quality. So squashes that have lower dry matter tend to be watery. When you cook them, you end up with a lot of water in the bottom of the baking pan, and then the flavor just kind of tastes watery. So there’s a dry matter test that I do, which is: you cut a small piece of a given squash that you want to test, and you weigh it, and then you dehydrate it completely and you weigh it again. So you can calculate the percentage of the weight that’s made up of just dry matter once you’ve completely dehydrated it. And usually the good quality eating squash is going to be at least 11% or 12% dry matter, up to about 20%. And when you start to get below 10%, people are going to probably think of it as kind water or bland.

I don’t always actually do that dry matter test, because I can get a sense of it just by doing a taste test, but it’s a good way to get started. If you have a whole lot of different squashes that you’re trying to compare and keep data on, you can do dry matter tests and have a number there to compare the squash quality.

Rachel Hultengren: So ‘Waltham’ has good dry matter and good flavor, and the Seminole Pumpkin has this disease resistance that you were hoping to get into a ‘Waltham’- like squash.

Edmund Frost: Yeah, there’s a little more to it. I find that ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ usually also has good flavor and dry matter, but it also has a very large seed cavity, so the amount of edible squash that you get out of it per pumpkin is pretty low. Also it’s not the butternut shape that people are used to. And it’s not just the dry matter test that I do to evaluate the squash; I’ll also do a sugar test – a Brix test. I have a Brix meter. And that’s also an important way to get data about how the different squashes compare.

And then, in addition to that, I taste them, because sometimes there are squashes that have good dry matter and good sweetness but I just think don’t taste quite right. So it’s all three of those methods together.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah, actually eating the squash is a really important part before deciding that it’s something that other people might want to eat.

Edmund Frost: Right. And it has to be cooked – you can’t really get a good sense of it by sampling the raw squash.

Rachel Hultengren: Have you tried?

Edmund Frost: Yeah, I have tried.

Rachel Hultengren: How was it?

Edmund Frost: When you just try raw squash, you can get a sense of the sweetness, but the flavor is just gonna be really different when it’s cooked. And also when you try raw squash you don’t get any sense of texture or dry matter of the cooked squash.

Rachel Hultengren: Mmhmm. So it’s not bad?

Edmund Frost: Eating the raw squash?

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah – was that pleasant?

Edmund Frost: Yeah, I like eating raw squash. As I’m working with squash, I’ll often nibble on it a bit, partly to get a sense of the sweetness and partly just because I like to eat it. But I haven’t really used it to make a meal out of, or to make dishes out of, though I think that could be something to explore.

Rachel Hultengren: So you’ve said that after you saw the ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ doing well despite the downy mildew in the field, and you were growing ‘Waltham’ as a produce crop, and you thought maybe the two of these could be good parents in a new project to develop a new variety of butternut squash – tell me more about the process of getting that project started.

Edmund Frost: So, yeah. When I started I knew very little about plant breeding, and I didn’t actually know how to do hand pollinations. So I just planted some Seminole next to the ‘Waltham’ produce crop that I was growing. So it was a planting that was mostly ‘Waltham’, with a few ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ plants, and then I saved seed from some of the ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ fruits. And then the next year, I planted out that seed and I saved seed from the fruits that had gotten the ‘Waltham’ shape into them, which was most of them.

Rachel Hultengren: So you weren’t doing those hand pollinations, where you move pollen from one plant that you want to be a parent onto the female parts of the other plant that you want to be a parent, but by growing them close to one another, because there are insects (mostly bees) flying between the flowers of the different plants, you were confident that at least some of the pollen from ‘Waltham’ would get on to at least some of the flowers of the ‘Seminole Pumpkins’?

Edmund Frost: Right. At least that was my hope… but yeah, I expected there would be at least some crossing. And there was a good bit of crossing, so it was a perfectly adequate way of starting. And then I, kind of, worked on it every year since then, and every year I’ve gotten a little bit more knowledge about how to do selections. And so I’ve learned a whole lot more about the process since 2011, when I started.

Rachel Hultengren: I think that’s a common story, is for folks that are interested in a plant breeding project and get going – we learn a lot as we go. And that can be really positive; we don’t have to have all the information just to get started. We can learn a lot and see where the projects take us.

Edmund Frost: And it can take so long to get started on a new variety. It can be just really useful to make those crosses happen, and then you’ve got all winter to think about what to do next. So you’ve got plenty of time to research and talk to people and learn the process.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah. So you planted out the seeds that you had gotten from the ‘Seminole Pumpkin’, and when those plants grew up and put on fruit, you looked for the plants that had fruit that looked like ‘Waltham’, which to you indicated that those had been crossed by the bees. And then you said that you saved seeds from those plants and planted those out. Is that the same process that you took every year that you did selections?

Edmund Frost: No, not exactly. The first year of growing the cross was 2012, and I just looked for fruits that had a shape somewhere in between ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ and ‘Waltham’, and that indicated that they’d been crossed, and saved seed from those. And then I took that seed and planted it out in 2013 and that’s when… Each year I got a little bit more involved in the selection. So the first year, in 2012, I was just looking for stuff that had been crossed. If I had done the cross by hand, I wouldn’t have had to even do any selection; I could have just known that it was all crossed and just saved the seed. The first generation after you make a cross – the F1 hybrid – is generally uniform, and it’s not… you don’t start making selections that year. So the first two years of the breeding project, where you make the cross and then you grow out the F1, you can be working with pretty small numbers of plants and not actually doing a lot of selection work. But then starting in the second generation after the cross, which is the F2 generation, that’s when a whole lot of genetic diversity shows up in the plants, and that’s when you start doing selection.

Rachel Hultengren: What did that F2 generation look like?

Edmund Frost: So there were some that looked kind of like ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’, there were some that looked like a butternut. I remember that there was also variation in size. I remember some pretty large-fruited ones. Again, I was just getting started in the process, so I didn’t have a huge grow-out. I think that was maybe 40 or 50 plants in the F2 generation, and my selection that year was just to find the plants that survived and still had vines that were alive at frost. And to me that indicated that they had good disease resistance. But I was just letting all the plants intertwine with each other at that point. So when I went out to do the harvest and the evaluation, I had to track down where the fruits were from each plant, which took a little while.

Rachel Hultengren: That can be really difficult.

Edmund Frost: Yeah, it’s not necessarily the way I recommend doing it. It’s not the way I do it anymore, but I think it was actually a fairly functional way to start the project. You know, some of the plants were completely dead in early October, and some of them were still pretty alive and had good yields of fruits. So that was my first year of selection. And I didn’t even really get into eating quality that year; I was just looking at plants that could stay alive the whole season in the face of the downy mildew pressure, and also shape and productivity that first season of selection.

Rachel Hultengren: After that first season of selection, did you have a population that was fairly uniform for downy mildew resistance, or is that a trait that you have continued to select on?

Edmund Frost: I have continued to select on that. And I wouldn’t say that it was uniform, but it was already a big improvement. I saved seed from the second generation, and the seed you save from the second generation from the cross is called ‘F3 seed’. And I did a big winter squash variety trial in 2014, and that F3 seed of the ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ x ‘Waltham’ cross did very well for downy mildew resistance, especially well compared to the ‘Waltham’, but it was even close to the ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ for downy mildew resistance. So yeah, I was very pleased that it was already starting to work at that point.

Rachel Hultengren: And by ‘variety trial’, for those who haven’t conducted one, you just mean to grow as many different varieties that fit what you’re looking for as you have space for, and just planting many plots of the crop – one plot per variety or a couple of plots per variety if you have the space – and comparing all of the traits that you’re interested in between those many varieties all growing at the same time in the same field.

Edmund Frost: Yeah, that’s right. And there’s different kinds of variety trials you can do. A more formal variety trial will be one where you have each variety planted in several different locations. And that can kind of help you confirm the data that you’re getting. But you can also do what’s called an ‘observation trial’, where you just grow one plot of each thing and take data or make observations. And in a lot of cases, that can be adequate for getting a sense of things. So it’s kind of a matter of what you have space and resources to do. But really just getting out there and trying things.

And Organic Seed Alliance has a really good little manual that’s free on their website about how to set up a variety trial, and I definitely recommend looking at that.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah, I’ll share a link to that in the show-notes.

Edmund Frost: Great.

Rachel Hultengren: So in the variety trials, you grew a patch or a plot of this F3 seed from your cross next to or close to a patch of ‘Waltham’ and a patch of ‘Seminole Pumpkin’ so you could see them and make direct comparisons of how they did that year in the field.

Edmund Frost: Right. It was a trial that included 20 or so other squash varieties as well.

Rachel Hultengren: Those other 20 varieties – did those not do very well with the downy mildew?

Edmund Frost: What I found in that trial, and have seen since, is that there are actually a lot of tropical varieties of Cucurbita moschata that are pretty downy mildew resistant, and I had some of those included in the trial that did well for downy mildew. There’s different issues they have to make them maybe not ideal for growing here. Some of them have splitting issues, most of them are very large fruited – which is not what a lot of market growers are looking for in this country – and the eating quality is… can be variable, too. So yeah, this is kind of a long answer, but in that 2014 trial, there were tropical varieties that did well for downy mildew, but the temperate varieties I tried didn’t do well for downy mildew, and that especially includes for ‘Waltham’.

Starting in 2015 and every year since then, I’ve done a much more intensive breeding trial, where I have usually about 100 plants that I train separately and evaluate separately. So, you know, looking at the productivity and fruit shape, fruit shape and all the eating quality. I’m just testing and tasting several squash from each of the promising plants out there. Also looking at the downy mildew on the foliage. And I’m in my fifth year of that more intensive selection that includes the big eating quality focus. You know, I think I got a good start early on, in terms of finding downy mildew resistance, but these last 5 years have kind of been central to making the variety what it is in terms of combination of productivity, eating quality and downy mildew resistance.

Rachel Hultengren: Do you do the taste testing by yourself, or do you have other folks that help you with that?

Edmund Frost: Yeah, I like to have other people’s input just so it’s not only what I like, but it’s important that I taste everything so that I know how everything compares to each other.

Rachel Hultengren: How do you prepare the squash for taste-testing?

Edmund Frost: I bake the squash. And when I’m testing a whole lot of different fruits at the same time, I’ll usually cut off a portion of the end of the squash, so I can fit maybe a dozen or more squash on the same baking pan. And I’ll bake them at 375 (degrees Fahrenheit) and make sure they’re fully cooked when I bring them out of the oven and let them cool a little bit and then I can go ahead and taste them.

Rachel Hultengren: I know a lot of people eat squash with things like brown sugar or maple syrup. Do you use those when you do taste testing?

Edmund Frost: No, I just taste them plain. And I’m really going for a squash that doesn’t need those things added, that’s sweet and rich and flavorful and is good eating without anything added.

Rachel Hultengren: Do you have any advice on how to pick the best butternut at the grocery store or the farmers’ market? Is there any correlation between how it looks on the outside and how it tastes on the inside?

Edmund Frost: Yeah, so riper butternuts are usually a darker color, so look for dark color, so that’s the main piece of advice I could give. There’s a lot of butternuts on the market that are picked too immature and aren’t very good eating quality. There are a lot of butternuts that have been grown in high downy mildew conditions that aren’t good eating quality.

Rachel Hultengren: Right, because you said that when the downy mildew comes and the plants die earlier than they would have otherwise, the fruit don’t get as much sugar as they would have.

Edmund Frost: Right.

Rachel Hultengren: So that’s probably pretty hard to tell at a grocery store, but if you go to a farmers’ market, and are able to talk with your farmer, you can ask them what varieties they’re growing and see how they’re handling the downy mildew.

Edmund Frost: Yeah, that could help, but there’s not many downy mildew resistant varieties available. So I guess you could just ask them, ‘How was your crop this year?’ And if they feel like it was a healthy crop, they’re more likely to be tasty butternuts. So that, and color.

Rachel Hultengren: How do farmers conventionally manage downy mildew? So if they don’t have resistant varieties, is there anything that a farmer can do to save their crop from the disease?

Edmund Frost: I’m an organic farmer, and even as an organic farmer, I don’t really use disease control sprays. There may be products available now that will give results on an organic farm; it’s not my focus. And in conventional farming, it’s my understanding that there are fungicides that are widely used for downy mildew, and that they’re used in actually pretty large quantities on a pretty regular basis. Part of my work is focused on trying to decrease the amount of those kind of chemicals that people are spraying.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah, that points to the fact that it’s a really powerful tool to have disease resistant varieties on an organic farm, because there might not be other disease management tools available, or those tools might not be very effective, or even if they are, a farmer might just not want to use any pesticides or fungicides on their farm, even those that are listed by the Organic Materials Review Institute and allowed in certified-organic production.

Edmund Frost: Right. You know, I didn’t exhaustively try different disease control sprays for downy mildew, but what I tried didn’t really make a dent in it, and it’s my understanding that the organic options for downy mildew control don’t… aren’t super effective. So yeah, resistant varieties are, I think, key to dealing with certain diseases.

Rachel Hultengren: Now that you’re nine years into this project, how does ‘South Anna’ differ from either of its parents?

Edmund Frost: It’s very different from both parents. It has a lot darker color than ‘Waltham’, and part of that is that I’m always letting the fruits get really ripe because the plants are alive longer, and part of it is that ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’ has a darker color, and that’s gone into the ‘South Anna’. The shape is somewhat variable. They’re 98% some kind of butternut shape, but they’re a little more… variation on what the necks look like and on the fruit size than ‘Waltham’. And starting in 2015, I really brought in a big focus on eating quality, and I think that’s made a huge difference. And I think I have something that’s better eating quality than a ‘Waltham’, in terms of sweetness and dry matter, but also just… I really like the flavor of it.

Rachel Hultengren: And at this point, is ‘South Anna’ as disease resistant as the ‘Seminole Pumpkin’?

Edmund Frost: It’s been a few years since I grew ‘Seminole (Pumpkin)’; I think that it is at least as resistant. It would be good to check up on that, to grow them side by side again. They’re definitely more productive; you’re definitely getting a lot more fruit out of it, because the seed cavity is so much smaller and you’ve got a neck on them.

Rachel Hultengren: So are you… would you say you’re done with ‘South Anna’, or is it still a work in progress?

Edmund Frost: We started selling the variety as ‘South Anna’ in 2018, but it also is still a work in progress. So this year I’ve got 100 plants out there that are all trained separately. And right now it’s early October; I’m going through and harvesting each plant, looking at the fruits, looking at the foliage, seeing how alive it is. So each plant is going to get a foliage rating, I’ll have a yield number, I’ll have an average fruit size, I’ll have notes on shape. So yeah, I want the plants that have good foliage, good yields, good shape, and then the plants with those characteristics I’m gonna also do eating quality tests on.

So yeah, I’m still very much still at it in terms of the selection. And I may take it in a couple different directions. Growers that do butternut squash for processing, which is actually… when you buy a can of pumpkin pie filling, it’s usually butternut squash. So growers that grow for processing tend to want larger fruits, and especially care about productivity on a weight per acre basis. So I’m thinking of starting a line in that direction, and starting a line with smaller fruits for market growers, and probably keeping the somewhat more diverse line as ‘South Anna’.

Rachel Hultengren: Have you heard any feedback from farmers or gardeners who grew the variety the past couple of years?

Edmund Frost: Yeah, I’ve been getting feedback for several years on it. And I definitely hear that it has good disease resistance, that it holds up a lot better than regular butternuts to downy mildew, and that it’s really good eating quality. I’ve gotten a lot of positive feedback.

Rachel Hultengren: The farmers that you’ve gotten feedback from – are they mostly in the Southeast, or do you sell seeds to folks all across the U.S.?

Edmund Frost: Mostly in the Southeast, some in the Northeast. But I think that ‘South Anna’ is a little bit long season for northern New England, for instance.

Rachel Hultengren: What are the conditions like in Virginia where you’re growing?

Edmund Frost: Our last frost date in the spring is typically the first week of May, and our first frost is about October 20th. It’s very hot and humid in the summer; it can rain at anytime and it’s kind of variable how much it rains. We’re in a kind of a drought right now, but last year it was incredible rainy in the fall. Yeah, summer temperatures are usually in the high 80’s or low 90’s.

Rachel Hultengren: I’ve read that you’ve collaborated with university researchers on Cucurbit downy mildew work. At what stage of the process of developing downy mildew resistant squashes did those collaborations start, and what have they entailed?

Edmund Frost: So, (Dr.) Michael Mazourek from Cornell is the person that I’ve worked with the most, and he really helped orient me to understanding how to… how to work with winter squash and cucumbers. When I was doing the trials in 2014, he walked me through process of, ‘How do you do brix test? How do you do dry matter tests? How do you set up the variety trial?’ Yeah, I just got a lot of advice and mentorship from Michael. He was the person who told me that I needed to train the plants separately, and I want to explain that. Usually you let winter squash grow altogether, let all the plants intertwine. But when you’re doing selection work with Cucurbits, you usually want to be able to look at each plant separately. And with winter squash it’s really important because you want the best combination of eating quality and productivity, and if you don’t look at each plant separately, you might be selecting for one of those at the expense of the other.

So the other collaboration that Michael and I have had is that when I’ve done variety trials of both cucumbers and winter squash, he’s sent me some of their material to try out. And that’s useful to us because they’ve had some really good downy mildew resistant cucumbers especially, and it’s been helpful to them to be able to get information about how their material grows in Virginia conditions. So that’s been, you know, a mutually beneficial relationship.

And I’ve gotten ideas and input from other folks, as well.

Rachel Hultengren: How did you get connected with these folks?

Edmund Frost: I got connected with all these folks through Organic Seed Alliance. They have a conference every two years, it’s usually in Oregon. The first one I went to was 2012, and I think that’s where I met Michael Mazourek and we started to have a back and forth at that point.

Rachel Hultengren: I’d like to talk about the fact that you’ve pledged ‘South Anna’ as an open-source variety with the Open Source Seed Initiative. How did you first get involved in discussions about intellectual property, or start thinking yourself about this issue?

Edmund Frost: I’ve thought a lot about intellectual property with plants, especially around GMO’s. I was actually an anti-GMO activist before I was a seed grower. And I think a lot about food sovereignty and seed sovereignty, and you know, we have a situation where a small number of corporations control most of the seeds that people use. And a lot of gardeners and even most farmers – even most organic farmers – don’t really have the familiarity and the know-how to save their own seeds and work with their own seeds and do selection and do breeding work. So I really care about bringing some of that knowledge back, especially in my region. In the Southeast it’s especially important because most sustainable and organic seed companies are not located in the Southeast so they’re not researching or selecting or focusing on issues that we care about in the Southeast, so it makes it all the more important to do the work here.

So I’ve had those kind of ideas on my radar for a long time, and I think I first heard about OSSI, the Open Source Seed Initiative, at one of the Organic Seed Alliance conferences, and started thinking about it. And I definitely thought it was an interesting idea. And I think it was at the 2016 conference I ran into Carol Deppe, and she’s on the OSSI board, and I did a presentation about our squash work, and I got to talking with her about it and about ‘South Anna’. And she had some OSSI pledge forms right there and she talked me into doing it, which I’m, you know, thrilled about.

Rachel Hultengren: For folks who haven’t heard all of the episodes of this podcast, the Open Source Seed Initiative has a pledge that plant breeders can sign that expresses their intention to make their variety something that anyone can use for breeding work without restriction, and with the intention that no restrictive intellectual property rights will be claimed on that variety or on the results of any breeding project using that variety as a parent.

The pledge reads: You have the freedom to use these OSSI-Pledged seeds in any way you choose. In return, you pledge not to restrict others’ use of these seeds or their derivatives by patents or other means, and to include this pledge with any transfer of these seeds or their derivatives.

What do you see as being the impact of having signed this pledge for ‘South Anna’?

Edmund Frost: It’s my understanding that Monsanto breeders aren’t willing to work with OSSI-pledged varieties, and I think that’s huge. I’ve seen some of the kinds of utility patents that Monsanto has taken out on cucumbers, that are really upsetting, and I like the idea that this material isn’t going to be used in that way.

Rachel Hultengren: What’s the impact of Monsanto having those utility patents? What does that do to farmers or to other plant breeders?

Edmund Frost: I think it… my understanding of utility patents is that a lot of them wouldn’t stand up in court, but they’re granted by the (United States) Patent (and Trademark) Office, which is, you know, probably underfunded. And just the existence of these patents keeps people from doing whatever the patents say not to do.

So my example with the cucumbers is that there was a variety from India. It’s in the USDA’s seedbank; you can actually get it from the USDA seedbank. It has a number – it’s called 197088. And this has been known as a downy mildew resistant cucumber for a long time, at least since the 90’s. And it’s this little, round, russet colored cucumber. And it’s done well in trials as a downy mildew resistant variety, but it’s also very different from standard American cucumbers. So it’s not especially easy to use in a breeding project, and I’m not sure if people have used it for other breeding projects. But anyway, Monsanto used it recently to breed some of their new downy mildew resistant cucumbers. And they took out a utility patent on the idea of using this particular Indian cucumber variety as a downy mildew resistant source. So just the idea of using this as a parent in a cross, they claim is their… you know, they’re the only ones allowed to do this. Which is just crazy, because it’s… this is a variety that Indian peasant farmers have been working with for a long time; it’s already a cucumber; they’ve already been working with it as a downy mildew resistant variety because there’s downy mildew in India that they’re selecting against. But Monsanto took out this utility patent saying that they’re the only ones that are able to use this accession for downy mildew resistance breeding. It’s just… it’s just… there’s just so much… I don’t know. The audacity of it is just kind of stunning.

And, personally, I think there’s better downy mildew resistant cucumber sources that I’ve seen and that I’m working with, but the idea that Monsanto can say that they’re the only people that get to create new cucumbers with this variety that’s already a cucumber and just completely ignore the contribution of the farmers that created the variety is offensive. But I’ve talked with people who do work with cucumbers, and they’re not going to choose to work with this accession because of the utility patent. It’s just too much of a pain.

Rachel Hultengren: So the impact of university researchers not choosing to use that variety as a parent because it’s too much work or too difficult to work with material that has a utility patent on it – that means that there are possibly varieties that could work for farmers that won’t get developed or won’t get developed as quickly. That they’re having to work around these hurdles and barriers to be able to work on crops that are important and might be useful to farmers here.

Edmund Frost: Right. You know, with the example of this cucumber, there could be good varieties that public researchers could be coming up with based on this Indian accession, and they’re not going to use it now. And like I said, there’s other resistance sources that I think can work just fine. But yeah, the idea that Monsanto would be able to basically patent the use of a public domain variety that they have the benefit of having access to from the public domain is just ridiculous. So yeah, Open Source Seed Initiative is one way of countering these kinds of extreme privatization trends in seeds. And I would love it if people in different regions or with slightly different needs took ‘South Anna’ and selected it in different ways or crossed it with different things to come up with new useful varieties.

Rachel Hultengren: How did you decide on the name ‘South Anna’, and were there other names that you considered?

Edmund Frost: I knew it was going to be ‘South Anna’ pretty early on. South Anna is the name of the river near us, and I wanted to name something after the river. And I also liked that it had the word ‘south’ in it, ‘cause it’s… ‘South Anna’ is kind of a butternut for the South. So even though the name of the river is… it’s not called South Anna because it’s in the South – there’s a North Anna and a South Anna river – but I liked a variety with the name ‘South’ in it.

Rachel Hultengren: Mmhmm. Do you have any advice for someone wanting to start a breeding project, or any advice specifically for a would-be squash breeder?

Edmund Frost: I think variety trials are really important. And I don’t mean necessarily a formal variety trial, but finding out what’s out there. Because it could be that what you’re trying to breed for already exists – very likely it doesn’t already exist – but if you try out a lot of stuff, you’re gonna be able to find the best parents for your project. You know, like ‘South Anna’, there was one that had more of the eating quality characteristics that I wanted and one that had more of the disease resistance characteristics. But really, any two traits that are present in two different varieties that you want to combine, you can start a breeding project, cross them together and start selecting for those traits. But yeah, knowing what’s out there, having a good grasp on that, is a great way to start.

And then other advice is: come up with a need. I felt really fortunate to come across this clear need for downy mildew resistant Cucurbit varieties and felt like it was something that I was able to start working on that was important and also within my capacity to work on. So thinking of a concept: what’s really needed in your region, or in your situation, or in your system, and then coming up with ideas of how to get there?

I’ve read all of Carol Deppe’s books, and there’s a sense of, just, excitement and possibility of, like – you can just start doing this work! There’s so many things that you can make happen, and there’s a lot of need, and it’s really interesting and fun. And there are some complicated concepts, but they’re not that complicated. So I know that had a big influence on me as well, in terms of getting started with plant breeding, and I would recommend checking out her stuff.

Rachel Hultengren: Yeah, I’ll link to those in the show-notes also. Thanks for that. Do you have any final words for our listeners?

Edmund Frost: I would really like to encourage people to get into this work if they have any interest in it. It’s really fun and really interesting and really rewarding. And it’s really possible to come up with varieties that work a lot better than what’s already out there for your conditions. And there’s also just this huge need to do this work regionally. There’s not many plant breeders in the Southeast, of any kind, and I know that’s true for other regions as well. You know, if you love working with plants, I just think this is really interesting work to get into, especially if you identify a need that’s out there. So yeah, I just want to encourage people to do this work, and I would love to be available to talk to anyone about this. You can reach me at commonwealthseeds@gmail.com

Rachel Hultengren: Wonderful! That’s really generous of you. I hope that people take you up on it!

Edmund Frost: Yeah, me too!

Rachel Hultengren: Thanks so much, Edmund, for being on the show today – I really appreciate the time, and I’ve really enjoyed getting to hear more about ‘South Anna’.

Edmund Frost: Yeah, thank you! I really love getting to talk about this stuff.

Rachel Hultengren: I’ve been speaking today with Edmund Frost of Twin Oaks Seed Farm and Common Wealth Seed Growers about ‘South Anna Butternut’. Go to https://commonwealthseeds.com/ to find out how to buy seeds of the variety.

I should make a note here regarding Edmund’s references to Monsanto during our interview. Since it was purchased by Bayer in 2018, Monsanto no longer exists as a company name, but I didn’t think to clarify that while Edmund and I were talking.

Take a look at the show-notes to see photos of South Anna, including a striking picture of the 2014 variety trial that Edmund talked about. We also have links to the Organic Seed Alliance’s variety trial template that Edmund mentioned, and to Carol Deppe’s books. You can find those on the Open Source Seed Initiative’s website at www.osseeds.org. Full transcripts of each episode are also available there.

The Organic Seed Alliance’s Organic Seed Growers Conference, which Edmund mentioned, takes place every two years in Corvallis, Oregon, and will be happening next in February 2020. To learn more or to register to attend, go to https://seedalliance.org/conference/.

You can in touch with me at https://rachelhultengren.com. You can find and like the Open Source Seed Initiative on Facebook, and follow Free the Seed! on Spotify, or subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. Our theme music is by Lee Rosevere.

Thanks for listening! Until next time, I’m your host, Rachel Hultengren and this has been Free the Seed!